Regular Expressions¶

1. Regular Expressions¶

Regular expressions are a way to specify a set of strings that define a language.

There are three operators that can be used:

- \(+\) union (or)

- \(\cdot\) concatenation (AND)

- \(*\) star-closure (repeat 0 or more times)

We often omit showing the \(\cdot\) for concatenation.

Definition: Given \(\Sigma\),

- \(\emptyset\), \(\lambda\), and \(a \in \Sigma\) are R.E.

- If \(r\) and \(s\) are R.E. then

- \(r + s\) is R.E.

- \(r s\) is R.E.

- \((r)\) is R.E.

- \(r^*\) is R.E.

- \(r\) is a R.E iff it can be derived from (1) with a finite number of applications of (2).

Definition: \(L(r) =\) language denoted by R.E. \(r\).

\(\emptyset\), \(\{\lambda\}\), and \(\{a \in \Sigma\}\) are languages denoted by a R.E.

Note that \(\emptyset = \{\}\) (the empty set), while \(\lambda = \{ \lambda \}\), meaning the set containing just the empty string.

If \(r\) and \(s\) are R.E. then

- \(L(r + s) = L(r) \cup L(s)\)

- \(L(r s) = L(r) \cdot L(s)\)

- \(L((r)) = L(r)\)

- \(L((r)^*) = (L(r)^*)\)

1.2. Examples¶

\(\Sigma = \{a,b\}\), \(\{w \in {\Sigma}^{*} \mid w\) has an odd number of \(a\) 's followed by an even number of \(b\) 's \(\}\).

\((aa)^{*}a(bb)^{*}\)

\(\Sigma=\{a,b\}\), \(\{w \in {\Sigma}^{*} \mid w\) has no more than three \(a\) 's and must end in \(ab\}\).

\(b^{*}(ab^{*} + ab^{*}ab^{*} + \lambda)ab\)

Regular expression for positive and negative integers

\(0 + (- + \lambda)((1+2+\ldots +9)(0+1+2+\ldots +9)^{*})\)

What is acceptable, and not acceptable?

Now that we have defined what regular expressions are, a good question to ask is: Why do we need them? In particular, we already know two ways to define a language. One is conceptually, as an English description with more or less mathematical precision. The other is operationally in the form of a DFA (or equivalently, an NFA). So why yet another representation? A good answer is that the other two representations are deficient (in different ways) that the regular expression overcomes. Describing it in English is imprecise. Even if we use math to make it precise, its something that we cannot easily operationalize. On the other hand, defining a DFA (or NFA) is a bit time consuming. We can use a tool like JFLAP, but that takes a long time to work through the GUI, even if it is a relatively small machine. In contrast, we can type out a regular expression within a system like JFLAP. In that case, it is both fast to type and operationalizeable (in the sense that we can then implement the acceptor for the regular expression). Of course, while a program can be shorter or longer, it might be hard for us to come up with the program. In the same way, we might have to struggle to come up with the regular expression. But its probably short to type once we have it.

2. Regular Expressions vs. Regular Languages¶

Recall that we define the term regular language to mean the languages that are recognized by a DFA. (Which is the same as the languages recognized by an NFA.) How do regular expressions relate to these?

We can easily see NFAs for \(\emptyset\), \(\lambda\), and \(a \in \Sigma\) (see Linz Figure 3.1). But what about the "more interesting" regular expressions? And, can any regular language be described by a regular expression?

Theorem: Let \(r\) be a R.E. Then \(\exists\) NFA \(M\) such that \(L(M) = L(r)\).

Proof: By simple simulation/construction. (This is a standard approach to proving such things!)

We aleady know that we can easily do \(\emptyset\), \(\{\lambda\}\), and \(\{a\}\) for \(a \in \Sigma\).

Suppose that \(r\) and \(s\) are R.E. (By induction...) That means that there is an NFA for \(r\) and an NFA for \(s\).

- \(r + s\). Simply add a new start state and a new final state, each connected (in parallel) with \(\lambda\) transitions to both \(r\) and \(s\). [Linz 3.3]

- \(r \cdot s\). Add new start state and new final state, and connect them with \(\lambda\) transitions in series. [Linz 3.4]

- \(r^*\). Add new start and final states, along with \(\lambda\) transitions that allow free movement between them all. [Linz 3.5]

Example: \(ab^* + c\)

Note

Try this for yourself in JFLAP. Type in the R.E, then convert it to an NFA, then convert the NFA to a DFA, then minimize the DFA.

Theorem: Let \(L\) be regular. Then \(\exists\) R.E. such that \(L = L(r)\).

Perhaps you see that any regular expression can be implemented as a NFA. For most of us, its not obvious that any NFA can be converted to a regular expression.

Definition: A Generalized Transition Graph (GTG) is a transition graph whose edges can be labeled with any regular expression. Thus, it "generalizes" the standard transition graph. [See Linz 3.8]

Definition: A complete GTG is a complete graph, meaning that every state has a transition to every other state. Any GTG can be converted to a complete GTG by adding edges labeled \(\emptyset\) as needed.

Proof:

\(L\) is regular \(\Rightarrow \exists\) NFA \(M\) such that \(L = L(M)\).

Assume \(M\) has one final state, and \(q_0 \notin F\).

Convert \(M\) to a complete GTG.

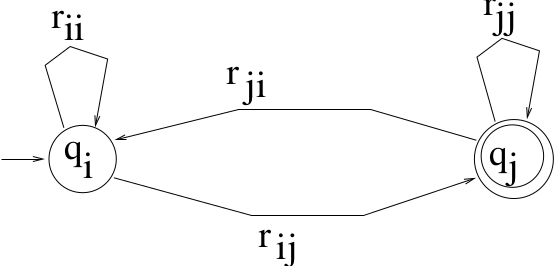

Let \(r_{ij}\) stand for the label of the edge from \(q_i\) to \(q_j\).

If the GTG has only two states, then it has this form:

Add an arrow to the start state. Then, the corresponding regular expression is:

\(r = (r^*_{ii}r_{ij}r^*_{jj}r_{ji})^*r^*_{ii}r_{ij}r^*_{jj}\)

Of course, we might have a machine with its start state also a final state. There are two ways to deal with this. One is to come up with a rule in this case. (Hint: Its the same rule, with an extra "OR" added for the case where we stay in the start state.) The other is to first convert our NFA to one with a single final state (separate from the start state). This is really easy to do, and is probably a homework problem for the class.

If the GTG has three states, then it must have the following form:

In this case, make the following replacements:

\[\begin{split}\begin{array}{lll} REPLACE & \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ & WITH \\ \hline r_{ii} && r_{ii}+r_{ik}r_{kk}^{*}r_{ki} \\ r_{jj} && r_{jj}+r_{jk}r_{kk}^{*}r_{kj} \\ r_{ij} && r_{ij}+r_{ik}r_{kk}^{*}r_{kj} \\ r_{ji} && $r_{ji}+r_{jk}r_{kk}^{*}r_{ki} \\ \end{array}\end{split}\]After these replacements, remove state \(q_k\) and its edges.

If the GTG has four or more states, pick any state \(q_k\) that is not the start or the final state. It will be removed. For all \(o \neq k, p \neq k\), replace \(r_{op}\) with \(r_{op} + r_{ok}r^*_{kk}r_{kp}\).

When done, remove \(q_k\) and all its edges. Continue eliminating states until only two states are left. Finish with step (3).

In each step, we can simplify regular expressions \(r\) and \(s\) with any of these rules that apply:

\(r + r = r\) (OR a subset with itself is the same subset)\(s + r{}^{*}s = r{}^{*}s\) (OR a subset with a bigger subset is just the bigger subset)\(r + \emptyset = r\) (OR a subset with the empty set is just the subset)\(r\emptyset = \emptyset\) (Intersect a subset with the empty set yields the empty set)\(\emptyset^{*} = \{\lambda\}\) (Special case)\(r\lambda = r\) (Traversing a R.E. and then doing a free transition is just the same R.E.)\((\lambda + r)^{*} = r^{*}\) (Taking a free transition adds nothing.)\((\lambda + r)r^{*} = r^{*}\) (Being able to do an option extra \(r\) adds nothing)And similar rules.

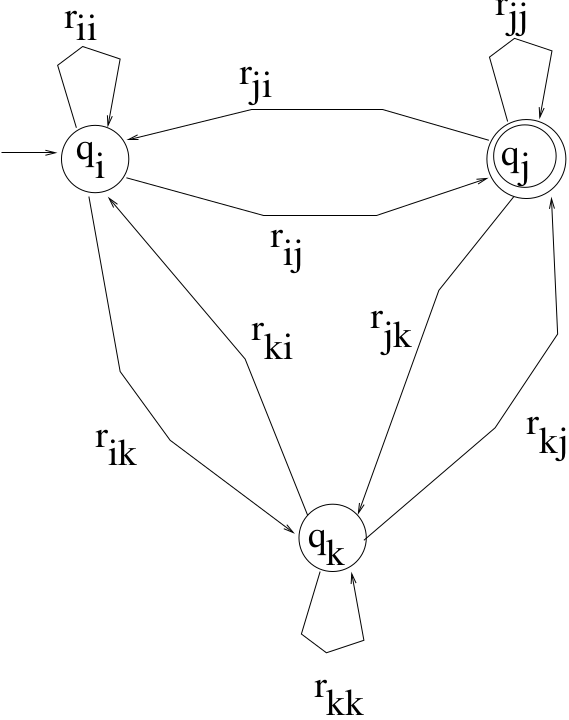

You should convince yourself that, in this image, the right side is a proper re-creation of the left side. In other words, the R.E labeling the self-loop for the left state in the right machine is correctly characterizing all the ways that one can remain in state \(q_0\) of the left machine. Likewise, the R.E. labeling the edge from the left state to the right state in the machine on the right is correctly characterizing all the ways that one can go from \(q_0\) to \(q_2\) in the machine on the right.

We have now demonstrated that R.E. is equivalent (meaning, goes both directions) to DFA.