30.2. The Fast Fourier Transform¶

30.2.1. The Fast Fourier Transform¶

See the FFT Storyboard for some more visualizations of this material.

Multiplication is considerably more difficult than addition. The cost to multiply two \(n\)-bit numbers directly is \(O(n^2)\), while addition of two \(n\)-bit numbers is \(O(n)\).

Recall that one property of logarithms is that \(\log nm = \log n + \log m\). Thus, if taking logarithms and anti-logarithms were cheap, then we could reduce multiplication to addition by taking the log of the two operands, adding, and then taking the anti-log of the sum.

Under normal circumstances, taking logarithms and anti-logarithms is expensive, and so this reduction would not be considered practical. However, this reduction is precisely the basis for the slide rule. The slide rule uses a logarithmic scale to measure the lengths of two numbers, in effect doing the conversion to logarithms automatically. These two lengths are then added together, and the inverse logarithm of the sum is read off another logarithmic scale. The part normally considered expensive (taking logarithms and anti-logarithms) is cheap because it is a physical part of the slide rule. Thus, the entire multiplication process can be done cheaply via a reduction to addition. In the days before electronic calculators, slide rules were routinely used by scientists and engineers to do basic calculations of this nature.

Now consider the problem of multiplying polynomials. A vector \(\mathbf a\) of \(n\) values can uniquely represent a polynomial of degree \(n-1\), expressed as

Alternatively, a polynomial can be uniquely represented by a list of its values at \(n\) distinct points. Finding the value for a polynomial at a given point is called evaluation. Finding the coefficients for the polynomial given the values at \(n\) points is called interpolation.

To multiply two \(n-1\)-degree polynomials \(A\) and \(B\) normally takes \(\Theta(n^2)\) coefficient multiplications. However, if we evaluate both polynomials (at the same points), we can simply multiply the corresponding pairs of values to get the corresponding values for polynomial \(AB\).

Example 30.2.1

Polynomial A: \(x^2 + 1\).

Polynomial B: \(2x^2 - x + 1\).

Polynomial AB: \(2x^4 - x^3 + 3x^2 - x + 1\).

When we multiply the evaluations of \(A\) and \(B\) at points 0, 1, and -1, we get the following results.

These results are the same as when we evaluate polynomial \(AB\) at these points.

Note that evaluating any polynomial at 0 is easy. If we evaluate at 1 and -1, we can share a lot of the work between the two evaluations. But we would need five points to nail down polynomial \(AB\), since it is a degree-4 polynomial. Fortunately, we can speed processing for any pair of values \(c\) and \(-c\). This seems to indicate some promising ways to speed up the process of evaluating polynomials. But, evaluating two points in roughly the same time as evaluating one point only speeds the process by a constant factor. Is there some way to generalized these observations to speed things up further? And even if we do find a way to evaluate many points quickly, we will also need to interpolate the five values to get the coefficients of \(AB\) back.

So we see that we could multiply two polynomials in less than \(\Theta(n^2)\) operations if a fast way could be found to do evaluation/interpolation of \(2n - 1\) points. Before considering further how this might be done, first observe again the relationship between evaluating a polynomial at values \(c\) and \(-c\). In general, we can write \(P_a(x) = E_a(x) + O_a(x)\) where \(E_a\) is the even powers and \(O_a\) is the odd powers. So,

The significance is that when evaluating the pair of values \(c\) and \(c\), we get

Thus, we only need to compute the \(E\) s and \(O\) s once instead of twice to get both evaluations.

The key to fast polynomial multiplication is finding the right points to use for evaluation/interpolation to make the process efficient. In particular, we want to take advantage of symmetries, such as the one we see for evaluating \(x\) and \(-x\). But we need to find even more symmetries between points if we want to do more than cut the work in half. We have to find symmetries not just between pairs of values, but also further symmetries between pairs of pairs, and then pairs of pairs of pairs, and so on.

Recall that a complex number \(z\) has a real component and an imaginary component. We can consider the position of \(z\) on a number line if we use the \(y\) dimension for the imaginary component. Now, we will define a primitive nth root of unity if

- \(z^n = 1\) and

- \(z^k \neq 1\) for \(0 < k < n\).

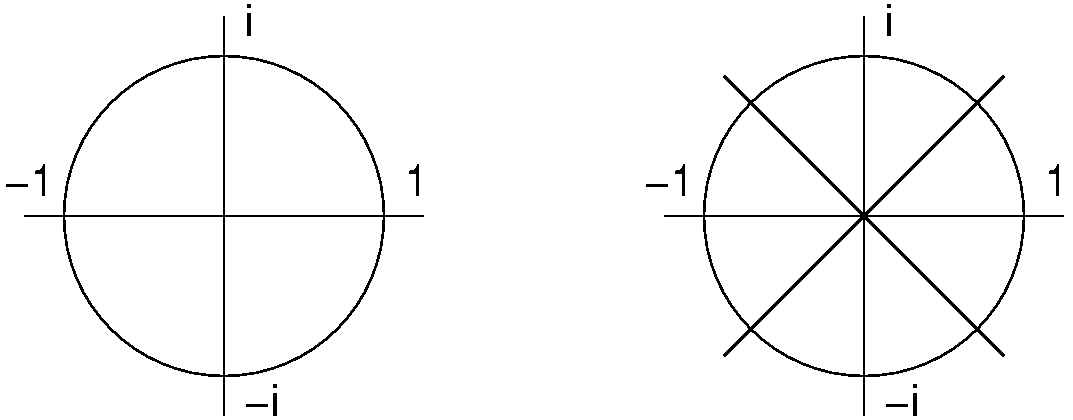

\(z^0, z^1, ..., z^{n-1}\) are called the nth roots of unity. For example, when \(n=4\), then \(z = i\) or \(z = -i\). In general, we have the identities \(e^{i\pi} = -1\), and \(z^j = e^{2\pi ij/n} = -1^{2j/n}\). The significance is that we can find as many points on a unit circle as we would need (see Figure 30.2.1). But these points are special in that they will allow us to do just the right computation necessary to get the needed symmetries to speed up the overall process of evaluating many points at once.

The next step is to define how the computation is done. Define an \(n \times n\) matrix \(A_{z}\) with row \(i\) and column \(j\) as

The idea is that there is a row for each root (row \(i\) for \(z^i\)) while the columns correspond to the power of the exponent of the :math`x` value in the polynomial. For example, when \(n = 4\) we have \(z = i\). Thus, the \(A_{z}\) array appears as follows.

Let \(a = [a_0, a_1, ..., a_{n-1}]^T\) be a vector that stores the coefficients for the polynomial being evaluated. We can then do the calculations to evaluate the polynomial at the \(n\) th roots of unity by multiplying the \(A_{z}\) matrix by the coefficient vector. The resulting vector \(F_{z}\) is called the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) for the polynomial.

When \(n = 8\), then \(z = \sqrt{i}\), since \(\sqrt{i}^8 = 1\). So, the corresponding matrix is as follows.

We still have two problems. We need to be able to multiply this matrix and the vector faster than just by performing a standard matrix-vector multiplication, otherwise the cost is still \(n^2\) multiplies to do the evaluation. Even if we can multiply the matrix and vector cheaply, we still need to be able to reverse the process. That is, after transforming the two input polynomials by evaluating them, and then pair-wise multiplying the evaluated points, we must interpolate those points to get the resulting polynomial back that corresponds to multiplying the original input polynomials.

The interpolation step is nearly identical to the evaluation step.

We need to find \(A_{z}^{-1}\). This turns out to be simple to compute, and is defined as follows.

In other words, interpolation (the inverse transformation) requires the same computation as evaluation, except that we substitute \(1/z\) for \(z\) (and multiply by \(1/n\) at the end). So, if we can do one fast, we can do the other fast.

If you examine the example \(A_z\) matrix for \(n=8\), you should see that there are symmetries within the matrix. For example, the top half is identical to the bottom half with suitable sign changes on some rows and columns. Likewise for the left and right halves. An efficient divide and conquer algorithm exists to perform both the evaluation and the interpolation in \(\Theta(n \log n)\) time. This is called DFT. It is a recursive function that decomposes the matrix multiplications, taking advantage of the symmetries made available by doing evaluation at the \(n\) th roots of unity. The algorithm is as follows:

Fourier_Transform(double *Polynomial, int n) {

// Compute the Fourier transform of Polynomial

// with degree n. Polynomial is a list of

// coefficients indexed from 0 to n-1. n is

// assumed to be a power of 2.

double Even[n/2], Odd[n/2], List1[n/2], List2[n/2];

if (n==1) return Polynomial[0];

for (j=0; j<=n/2-1; j++) {

Even[j] = Polynomial[2j];

Odd[j] = Polynomial[2j+1];

}

List1 = Fourier_Transform(Even, n/2);

List2 = Fourier_Transform(Odd, n/2);

for (j=0; j<=n-1, J++) {

Imaginary z = pow(E, 2*i*PI*j/n);

k = j % (n/2);

Polynomial[j] = List1[k] + z*List2[k];

}

return Polynomial;

}

Thus, the full process for multiplying polynomials \(A\) and \(B\) using the Fourier transform is as follows.

Represent an \(n-1\) -degree polynomial as \(2n-1\) coefficients:

\[[a_0, a_1, ..., a_{n-1}, 0, ..., 0]\]Perform

Fourier_Transformon the representations for \(A\) and \(B\)Pairwise multiply the results to get \(2n-1\) values.

Perform the inverse

Fourier_Transformto get the \(2n-1\) degree polynomial \(AB\).