12.4. The Full Binary Tree Theorem¶

Some binary tree implementations store data only at the leaf nodes, using the internal nodes to provide structure to the tree. By definition, a leaf node does not need to store pointers to its (empty) children. More generally, binary tree implementations might require some amount of space for internal nodes, and a different amount for leaf nodes. Thus, to compute the space required by such implementations, it is useful to know the minimum and maximum fraction of the nodes that are leaves in a tree containing \(n\) internal nodes.

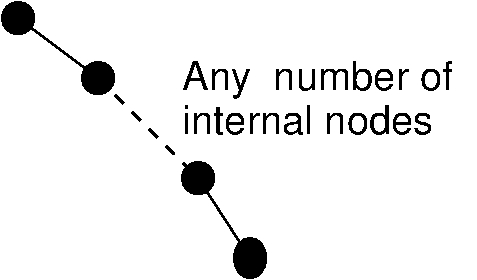

Unfortunately, this fraction is not fixed. A binary tree of \(n\) internal nodes might have only one leaf. This occurs when the internal nodes are arranged in a chain ending in a single leaf as shown in Figure 12.4.1. In this example, the number of leaves is low because each internal node has only one non-empty child. To find an upper bound on the number of leaves for a tree of \(n\) internal nodes, first note that the upper bound will occur when each internal node has two non-empty children, that is, when the tree is full. However, this observation does not tell what shape of tree will yield the highest percentage of non-empty leaves. It turns out not to matter, because all full binary trees with \(n\) internal nodes have the same number of leaves. This fact allows us to compute the space requirements for a full binary tree implementation whose leaves require a different amount of space from its internal nodes.

Figure 12.4.2: A tree containing many internal nodes and a single leaf.

Theorem 12.4.1

Full Binary Tree Theorem: The number of leaves in a non-empty full binary tree is one more than the number of internal nodes.

Proof: The proof is by mathematical induction on \(n\), the number of internal nodes. This is an example of the style of induction proof where we reduce from an arbitrary instance of size \(n\) to an instance of size \(n-1\) that meets the induction hypothesis.

- Base Cases: The non-empty tree with zero internal nodes has one leaf node. A full binary tree with one internal node has two leaf nodes. Thus, the base cases for \(n = 0\) and \(n = 1\) conform to the theorem.

- Induction Hypothesis: Assume that any full binary tree \(\mathbf{T}\) containing \(n-1\) internal nodes has \(n\) leaves.

- Induction Step: Given tree \(\mathbf{T}\) with \(n\) internal nodes, select an internal node \(I\) whose children are both leaf nodes. Remove both of \(I\)'s children, making \(I\) a leaf node. Call the new tree \(\mathbf{T}'\). \(\mathbf{T}'\) has \(n-1\) internal nodes. From the induction hypothesis, \(\mathbf{T}'\) has \(n\) leaves. Now, restore \(I\)'s two children. We once again have tree \(\mathbf{T}\) with \(n\) internal nodes. How many leaves does \(\mathbf{T}\) have? Because \(\mathbf{T}'\) has \(n\) leaves, adding the two children yields \(n+2\). However, node \(I\) counted as one of the leaves in \(\mathbf{T}'\) and has now become an internal node. Thus, tree \(\mathbf{T}\) has \(n+1\) leaf nodes and \(n\) internal nodes.

By mathematical induction the theorem holds for all values of \(n > 0\).

When analyzing the space requirements for a binary tree implementation, it is useful to know how many empty subtrees a tree contains. A simple extension of the Full Binary Tree Theorem tells us exactly how many empty subtrees there are in any binary tree, whether full or not. Here are two approaches to proving the following theorem, and each suggests a useful way of thinking about binary trees.

Theorem 12.4.2

The number of empty subtrees in a non-empty binary tree is one more than the number of nodes in the tree.

Proof 1: Take an arbitrary binary tree \(\mathbf{T}\) and replace every empty subtree with a leaf node. Call the new tree \(\mathbf{T}'\). All nodes originally in \(\mathbf{T}\) will be internal nodes in \(\mathbf{T}'\) (because even the leaf nodes of \(\mathbf{T}\) have children in \(\mathbf{T}'\)). \(\mathbf{T}'\) is a full binary tree, because every internal node of \(\mathbf{T}\) now must have two children in \(\mathbf{T}'\), and each leaf node in \(\mathbf{T}\) must have two children in \(\mathbf{T}'\) (the leaves just added). The Full Binary Tree Theorem tells us that the number of leaves in a full binary tree is one more than the number of internal nodes. Thus, the number of new leaves that were added to create \(\mathbf{T}'\) is one more than the number of nodes in \(\mathbf{T}\). Each leaf node in \(\mathbf{T}'\) corresponds to an empty subtree in \(\mathbf{T}\). Thus, the number of empty subtrees in \(\mathbf{T}\) is one more than the number of nodes in \(\mathbf{T}\).

Proof 2: By definition, every node in binary tree \(\mathbf{T}\) has two children, for a total of \(2n\) children in a tree of \(n\) nodes. Every node except the root node has one parent, for a total of \(n-1\) nodes with parents. In other words, there are \(n-1\) non-empty children. Because the total number of children is \(2n\), the remaining \(n+1\) children must be empty.