17.6. B-Trees¶

17.6.1. B-Trees¶

This section presents the B-tree. B-trees are usually attributed to R. Bayer and E. McCreight who described the B-tree in a 1972 paper. By 1979, B-trees had replaced virtually all large-file access methods other than hashing. B-trees, or some variant of B-trees, are the standard file organization for applications requiring insertion, deletion, and key range searches. They are used to implement most modern file systems. B-trees address effectively all of the major problems encountered when implementing disk-based search trees:

- B-trees are always height balanced, with all leaf nodes at the same level.

- Update and search operations affect only a few disk blocks. The fewer the number of disk blocks affected, the less disk I/O is required.

- B-trees keep related records (that is, records with similar key values) on the same disk block, which helps to minimize disk I/O on searches due to locality of reference.

- B-trees guarantee that every node in the tree will be full at least to a certain minimum percentage. This improves space efficiency while reducing the typical number of disk fetches necessary during a search or update operation.

A B-tree of order \(m\) is defined to have the following shape properties:

- The root is either a leaf or has at least two children.

- Each internal node, except for the root, has between \(\lceil m/2 \rceil\) and \(m\) children.

- All leaves are at the same level in the tree, so the tree is always height balanced.

The B-tree is a generalization of the 2-3 tree. Put another way, a 2-3 tree is a B-tree of order three. Normally, the size of a node in the B-tree is chosen to fill a disk block. A B-tree node implementation typically allows 100 or more children. Thus, a B-tree node is equivalent to a disk block, and a "pointer" value stored in the tree is actually the number of the block containing the child node (usually interpreted as an offset from the beginning of the corresponding disk file). In a typical application, the B-tree's access to the disk file will be managed using a buffer pool and a block-replacement scheme such as LRU.

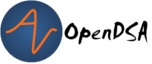

Figure 17.6.1 shows a B-tree of order four. Each node contains up to three keys, and internal nodes have up to four children.

Search in a B-tree is a generalization of search in a 2-3 tree. It is an alternating two-step process, beginning with the root node of the B-tree.

- Perform a binary search on the records in the current node. If a record with the search key is found, then return that record. If the current node is a leaf node and the key is not found, then report an unsuccessful search.

- Otherwise, follow the proper branch and repeat the process.

For example, consider a search for the record with key value 47 in the tree of Figure 17.6.1. The root node is examined and the second (right) branch taken. After examining the node at level 1, the third branch is taken to the next level to arrive at the leaf node containing a record with key value 47.

B-tree insertion is a generalization of 2-3 tree insertion. The first step is to find the leaf node that should contain the key to be inserted, space permitting. If there is room in this node, then insert the key. If there is not, then split the node into two and promote the middle key to the parent. If the parent becomes full, then it is split in turn, and its middle key promoted.

Note that this insertion process is guaranteed to keep all nodes at least half full. For example, when we attempt to insert into a full internal node of a B-tree of order four, there will now be five children that must be dealt with. The node is split into two nodes containing two keys each, thus retaining the B-tree property. The middle of the five children is promoted to its parent.

17.6.2. B+ Trees¶

The previous section mentioned that B-trees are universally used to implement large-scale disk-based systems. Actually, the B-tree as described in the previous section is almost never implemented. What is most commonly implemented is a variant of the B-tree, called the \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree. When greater efficiency is required, a more complicated variant known as the \(\mathrm{B}^*\) tree is used.

Consider again the linear index. When the collection of records will not change, a linear index provides an extremely efficient way to search. The problem is how to handle those pesky inserts and deletes. We could try to keep the core idea of storing a sorted array-based list, but make it more flexible by breaking the list into manageable chunks that are more easily updated. How might we do that? First, we need to decide how big the chunks should be. Since the data are on disk, it seems reasonable to store a chunk that is the size of a disk block, or a small multiple of the disk block size. If the next record to be inserted belongs to a chunk that hasn't filled its block then we can just insert it there. The fact that this might cause other records in that chunk to move a little bit in the array is not important, since this does not cause any extra disk accesses so long as we move data within that chunk. But what if the chunk fills up the entire block that contains it? We could just split it in half. What if we want to delete a record? We could just take the deleted record out of the chunk, but we might not want a lot of near-empty chunks. So we could put adjacent chunks together if they have only a small amount of data between them. Or we could shuffle data between adjacent chunks that together contain more data. The big problem would be how to find the desired chunk when processing a record with a given key. Perhaps some sort of tree-like structure could be used to locate the appropriate chunk. These ideas are exactly what motivate the \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree. The \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree is essentially a mechanism for managing a sorted array-based list, where the list is broken into chunks.

The most significant difference between the \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree and the BST or the standard B-tree is that the \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree stores records only at the leaf nodes. Internal nodes store key values, but these are used solely as placeholders to guide the search. This means that internal nodes are significantly different in structure from leaf nodes. Internal nodes store keys to guide the search, associating each key with a pointer to a child \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree node. Leaf nodes store actual records, or else keys and pointers to actual records in a separate disk file if the \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree is being used purely as an index. Depending on the size of a record as compared to the size of a key, a leaf node in a \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree of order \(m\) might have enough room to store more or less than \(m\) records. The requirement is simply that the leaf nodes store enough records to remain at least half full. The leaf nodes of a \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree are normally linked together to form a doubly linked list. Thus, the entire collection of records can be traversed in sorted order by visiting all the leaf nodes on the linked list. Here is a Java-like pseudocode representation for the \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree node interface. Leaf node and internal node subclasses would implement this interface.

An important implementation detail to note is that while

Figure 17.6.1 shows internal nodes containing three

keys and four pointers, class BPNode is slightly different in that

it stores key/pointer pairs.

Figure 17.6.1 shows the \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree as

it is traditionally drawn.

To simplify implementation in practice, nodes really do

associate a key with each pointer.

Each internal node should be assumed to hold in the leftmost position

an additional key that is less than or equal to any possible key value

in the node's leftmost subtree.

\(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree implementations typically store an

additional dummy record in the leftmost leaf node whose key value is

less than any legal key value.

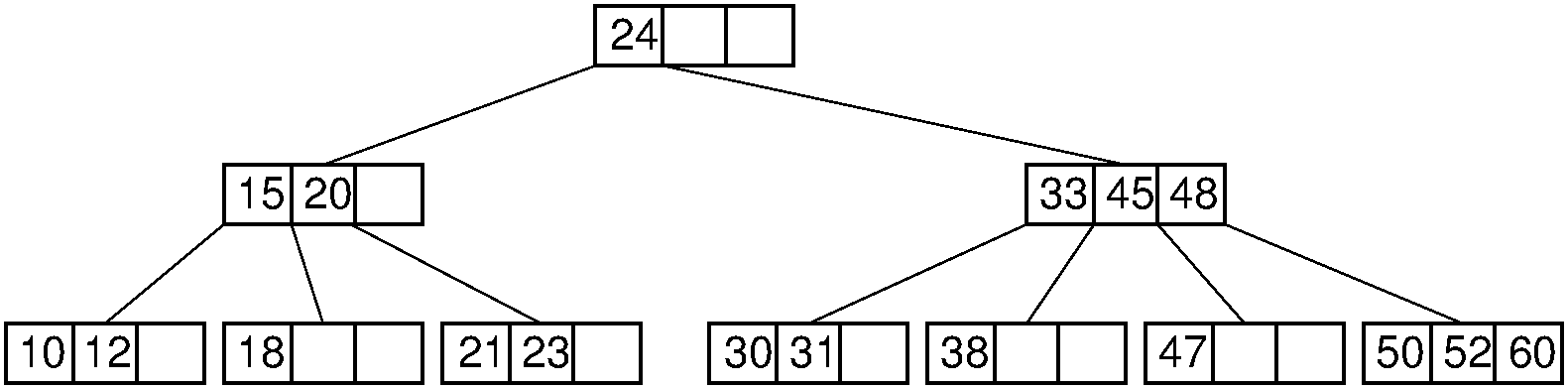

\(\mathrm{B}^+\) trees are exceptionally good for range queries. Once the first record in the range has been found, the rest of the records with keys in the range can be accessed by sequential processing of the remaining records in the first node, and then continuing down the linked list of leaf nodes as far as necessary. Figure 17.6.2 illustrates the \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree.

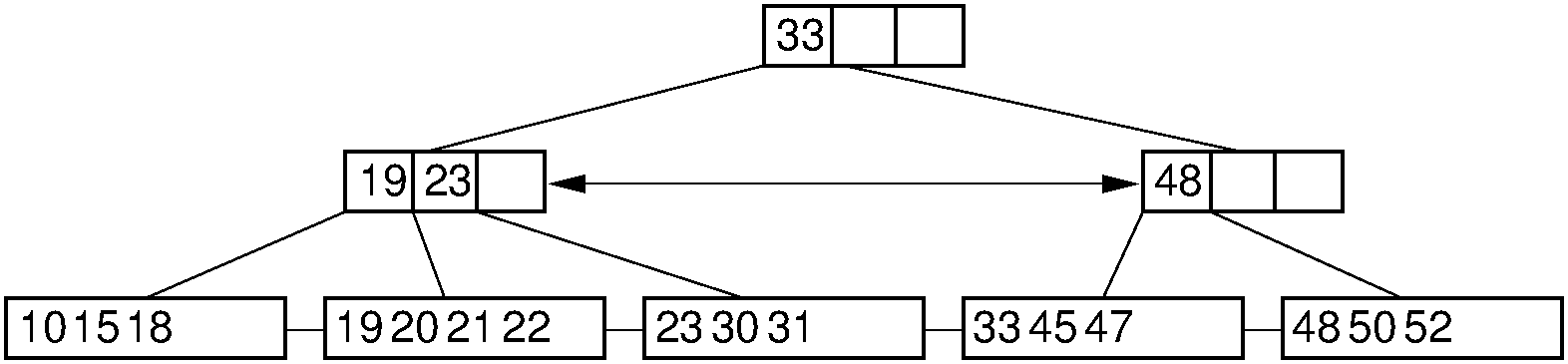

Figure 17.6.2: Example of a \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree of order four. Internal nodes must store between two and four children. For this example, the record size is assumed to be such that leaf nodes store between three and five records.

Search in a \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree is nearly identical to search in a regular B-tree, except that the search must always continue to the proper leaf node. Even if the search-key value is found in an internal node, this is only a placeholder and does not provide access to the actual record. To find a record with key value 33 in the \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree of Figure 17.6.2, search begins at the root. The value 33 stored in the root merely serves as a placeholder, indicating that keys with values greater than or equal to 33 are found in the second subtree. From the second child of the root, the first branch is taken to reach the leaf node containing the actual record (or a pointer to the actual record) with key value 33. Here is a pseudocode sketch of the \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree search algorithm.

\(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree insertion is similar to B-tree insertion. First, the leaf \(L\) that should contain the record is found. If \(L\) is not full, then the new record is added, and no other \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree nodes are affected. If \(L\) is already full, split it in two (dividing the records evenly among the two nodes) and promote a copy of the least-valued key in the newly formed right node. As with the 2-3 tree, promotion might cause the parent to split in turn, perhaps eventually leading to splitting the root and causing the \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree to gain a new level. \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree insertion keeps all leaf nodes at equal depth. Figure 17.6.3 illustrates the insertion process through several examples.

Figure 17.6.3: Examples of \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree insertion. (a) B-\(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree containing five records. (b) The result of inserting a record with key value 50 into the tree of (a). The leaf node splits, causing creation of the first internal node. (c) The \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree of (b) after further insertions. (d) The result of inserting a record with key value 30 into the tree of (c). The second leaf node splits, which causes the internal node to split in turn, creating a new root.

Here is a a Java-like pseudocode sketch of the \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree insert algorithm.

Here is an exercise to see if you get the basic idea of \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree insertion.

To delete record \(R\) from the \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree, first locate the leaf \(L\) that contains \(R\). If \(L\) is more than half full, then we need only remove \(R\), leaving \(L\) still at least half full. This is demonstrated by Figure 17.6.4.

Figure 17.6.4: Simple deletion from a \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree. The record with key value 18 is removed from the tree of Figure 17.6.2. Note that even though 18 is also a placeholder used to direct search in the parent node, that value need not be removed from internal nodes even if no record in the tree has key value 18. Thus, the leftmost node at level one in this example retains the key with value 18 after the record with key value 18 has been removed from the second leaf node.

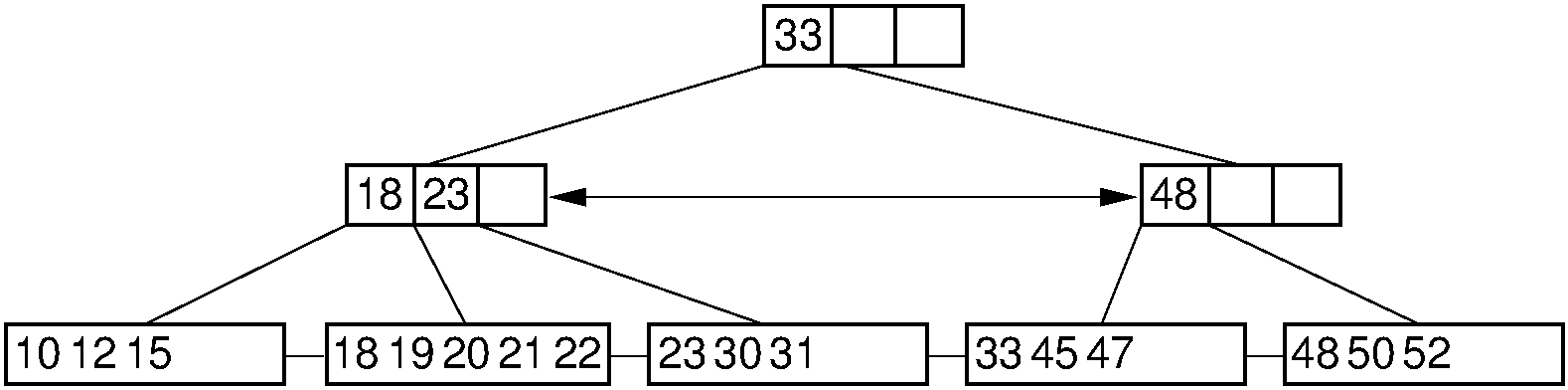

If deleting a record reduces the number of records in the node below the minimum threshold (called an underflow), then we must do something to keep the node sufficiently full. The first choice is to look at the node's adjacent siblings to determine if they have a spare record that can be used to fill the gap. If so, then enough records are transferred from the sibling so that both nodes have about the same number of records. This is done so as to delay as long as possible the next time when a delete causes this node to underflow again. This process might require that the parent node has its placeholder key value revised to reflect the true first key value in each node. Figure 17.6.5 illustrates the process.

Figure 17.6.5: Deletion from the \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree of Figure 17.6.2 via borrowing from a sibling. The key with value 12 is deleted from the leftmost leaf, causing the record with key value 18 to shift to the leftmost leaf to take its place. Note that the parent must be updated to properly indicate the key range within the subtrees. In this example, the parent node has its leftmost key value changed to 19.

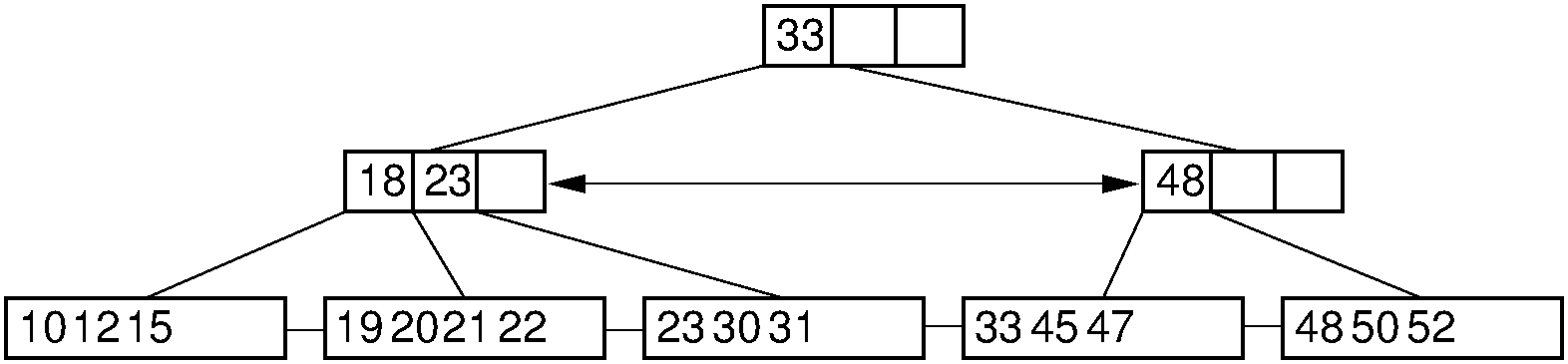

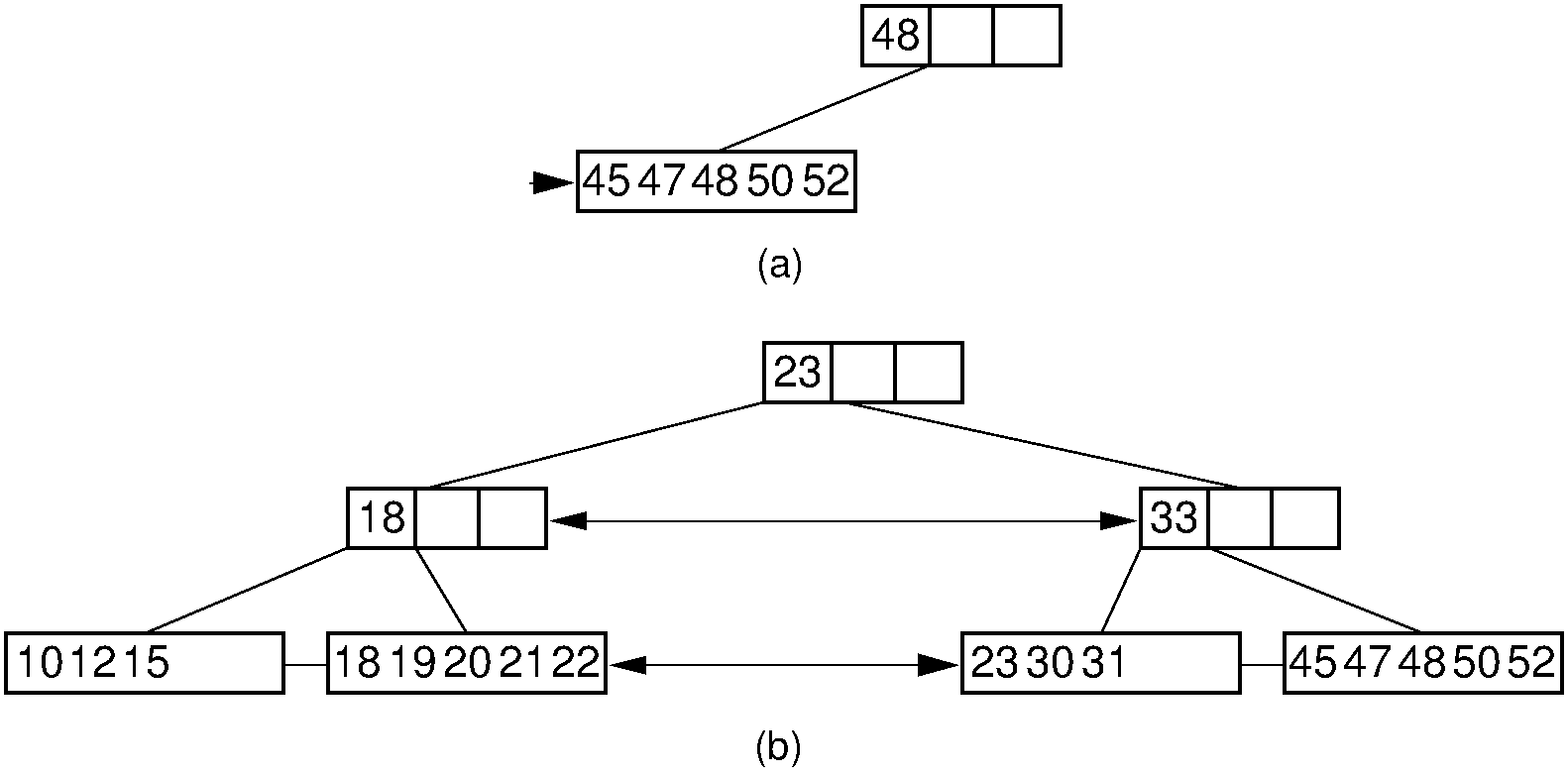

If neither sibling can lend a record to the under-full node (call it \(N\)), then \(N\) must give its records to a sibling and be removed from the tree. There is certainly room to do this, because the sibling is at most half full (remember that it had no records to contribute to the current node), and \(N\) has become less than half full because it is under-flowing. This merge process combines two subtrees of the parent, which might cause it to underflow in turn. If the last two children of the root merge together, then the tree loses a level. Figure 17.6.6 illustrates the node-merge deletion process.

Figure 17.6.6: Deleting the record with key value 33 from the \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree of Figure 17.6.2 via collapsing siblings. (a) The two leftmost leaf nodes merge together to form a single leaf. Unfortunately, the parent node now has only one child. (b) Because the left subtree has a spare leaf node, that node is passed to the right subtree. The placeholder values of the root and the right internal node are updated to reflect the changes. Value 23 moves to the root, and old root value 33 moves to the rightmost internal node.

Here is a Java-like pseudocode for the \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree delete algorithm.

The \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree requires that all nodes be at least half full (except for the root). Thus, the storage utilization must be at least 50%. This is satisfactory for many implementations, but note that keeping nodes fuller will result both in less space required (because there is less empty space in the disk file) and in more efficient processing (fewer blocks on average will be read into memory because the amount of information in each block is greater). Because B-trees have become so popular, many algorithm designers have tried to improve B-tree performance. One method for doing so is to use the \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree variant known as the \(\mathrm{B}^*\) tree. The \(\mathrm{B}^*\) tree is identical to the \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree, except for the rules used to split and merge nodes. Instead of splitting a node in half when it overflows, the \(\mathrm{B}^*\) tree gives some records to its neighboring sibling, if possible. If the sibling is also full, then these two nodes split into three. Similarly, when a node underflows, it is combined with its two siblings, and the total reduced to two nodes. Thus, the nodes are always at least two thirds full. [1]

Here is a visualization for the \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree.

This visualization was written by David Galles of the University of San Francisco as part of his Data Structure Visualizations package.

| [1] | This concept can be extended further if higher space utilization is required. However, the update routines become much more complicated. I once worked on a project where we implemented 3-for-4 node split and merge routines. This gave better performance than the 2-for-3 node split and merge routines of the \(\mathrm{B}^*\) tree. However, the spitting and merging routines were so complicated that even their author could no longer understand them once they were completed! |

17.6.3. B-Tree Analysis¶

The asymptotic cost of search, insertion, and deletion of records from B-trees, \(\mathrm{B}^+\) trees, and \(\mathrm{B}^*\) trees is \(\Theta(\log n)\) where \(n\) is the total number of records in the tree. However, the base of the log is the (average) branching factor of the tree. Typical database applications use extremely high branching factors, perhaps 100 or more. Thus, in practice the B-tree and its variants are extremely shallow.

As an illustration, consider a \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree of order 100 and leaf nodes that contain up to 100 records. A B-\(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree with height one (that is, just a single leaf node) can have at most 100 records. A \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree with height two (a root internal node whose children are leaves) must have at least 100 records (2 leaves with 50 records each). It has at most 10,000 records (100 leaves with 100 records each). A \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree with height three must have at least 5000 records (two second-level nodes with 50 children containing 50 records each) and at most one million records (100 second-level nodes with 100 full children each). A \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree with height four must have at least 250,000 records and at most 100 million records. Thus, it would require an extremely large database to generate a \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree of more than height four.

The \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree split and insert rules guarantee that every node (except perhaps the root) is at least half full. So they are on average about 3/4 full. But the internal nodes are purely overhead, since the keys stored there are used only by the tree to direct search, rather than store actual data. Does this overhead amount to a significant use of space? No, because once again the high fan-out rate of the tree structure means that the vast majority of nodes are leaf nodes. A K-ary tree has approximately \(1/K\) of its nodes as internal nodes. This means that while half of a full binary tree's nodes are internal nodes, in a \(\mathrm{B}^+\) tree of order 100 probably only about \(1/75\) of its nodes are internal nodes. This means that the overhead associated with internal nodes is very low.

We can reduce the number of disk fetches required for the B-tree even more by using the following methods. First, the upper levels of the tree can be stored in main memory at all times. Because the tree branches so quickly, the top two levels (levels 0 and 1) require relatively little space. If the B-tree is only height four, then at most two disk fetches (internal nodes at level two and leaves at level three) are required to reach the pointer to any given record.

A buffer pool could be used to manage nodes of the B-tree. Several nodes of the tree would typically be in main memory at one time. The most straightforward approach is to use a standard method such as LRU to do node replacement. However, sometimes it might be desirable to "lock" certain nodes such as the root into the buffer pool. In general, if the buffer pool is even of modest size (say at least twice the depth of the tree), no special techniques for node replacement will be required because the upper-level nodes will naturally be accessed frequently.