11.3. Sequential-Fit Methods¶

11.3.1. Sequential-Fit Methods¶

Sequential-fit methods attempt to find a “good” block to service a storage request. The three sequential-fit methods described here assume that the free blocks are organized into a doubly linked list, as illustrated by this figure.

There are two basic approaches to implementing the freelist. The simpler approach is to store the freelist separately from the memory pool. In other words, a simple linked-list implementation can be used, where each node of the linked list contains a pointer to a single free block in the memory pool. This is fine if there is space available for the linked list itself, separate from the memory pool.

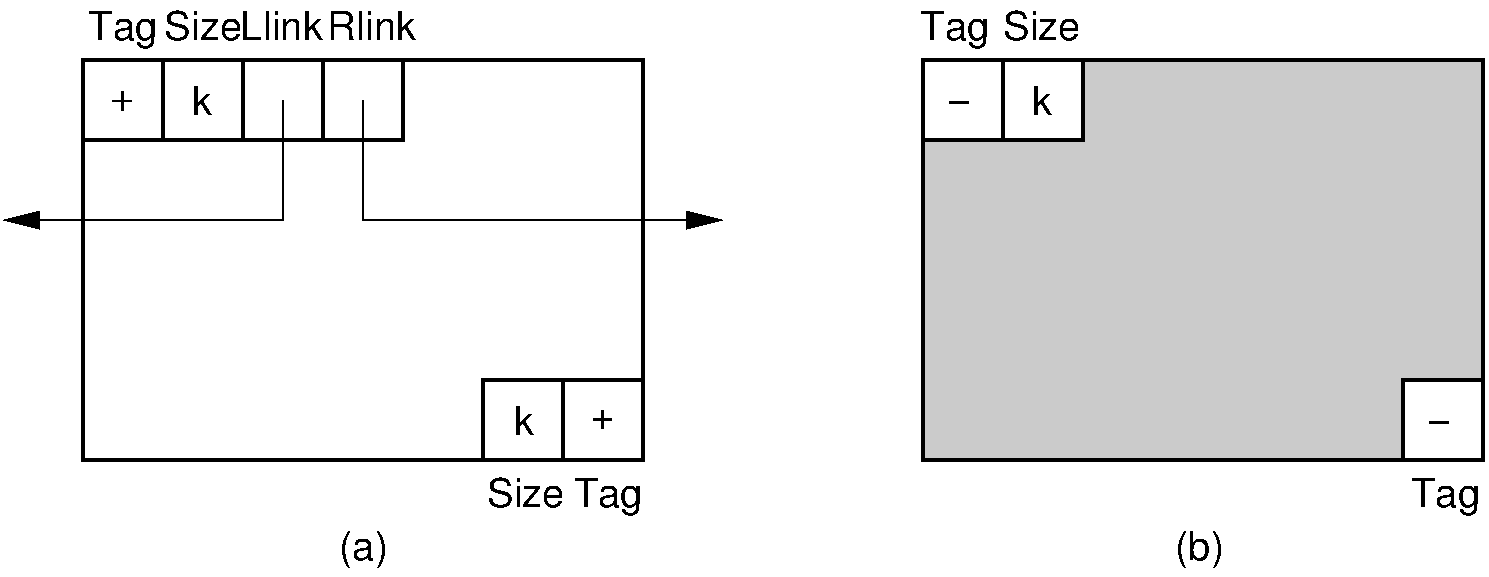

The second approach to storing the freelist is more complicated but saves space. Because the free space is free, it can be used by the memory manager to help it do its job; that is, the memory manager temporarily “borrows” space within the free blocks to maintain its doubly linked list. To do so, each unallocated block must be large enough to hold these pointers. In addition, it is usually worthwhile to let the memory manager add a few bytes of space to each reserved block for its own purposes. In other words, a request for \(m\) bytes of space might result in slightly more than \(m\) bytes being allocated by the memory manager, with the extra bytes used by the memory manager itself rather than the requester. We will assume that all memory blocks are organized as shown in the figure below, with space for tags and linked list pointers. Here, free and reserved blocks are distinguished by a tag bit at both the beginning and the end of the block, for reasons that will be explained. In addition, both free and reserved blocks have a size indicator immediately after the tag bit at the beginning of the block to indicate how large the block is. Free blocks have a second size indicator immediately preceding the tag bit at the end of the block. Finally, free blocks have left and right pointers to their neighbors in the free block list.

Figure 11.3.1: Blocks as seen by the memory manager. Each block includes additional information such as freelist link pointers, start and end tags, and a size field. (a) The layout for a free block. The beginning of the block contains the tag bit field, the block size field, and two pointers for the freelist. The end of the block contains a second tag field and a second block size field. (b) A reserved block of \(k\) bytes. The memory manager adds to these \(k\) bytes an additional tag bit field and block size field at the beginning of the block, and a second tag field at the end of the block.¶

The information fields associated with each block permit the memory manager to allocate and deallocate blocks as needed. When a request comes in for \(m\) words of storage, the memory manager searches the linked list of free blocks until it finds a “suitable” block for allocation. How it determines which block is suitable will be discussed below. If the block contains exactly \(m\) words (plus space for the tag and size fields), then it is removed from the freelist. If the block (of size \(k\)) is large enough, then the remaining \(k - m\) words are reserved as a block on the freelist, in the current location.

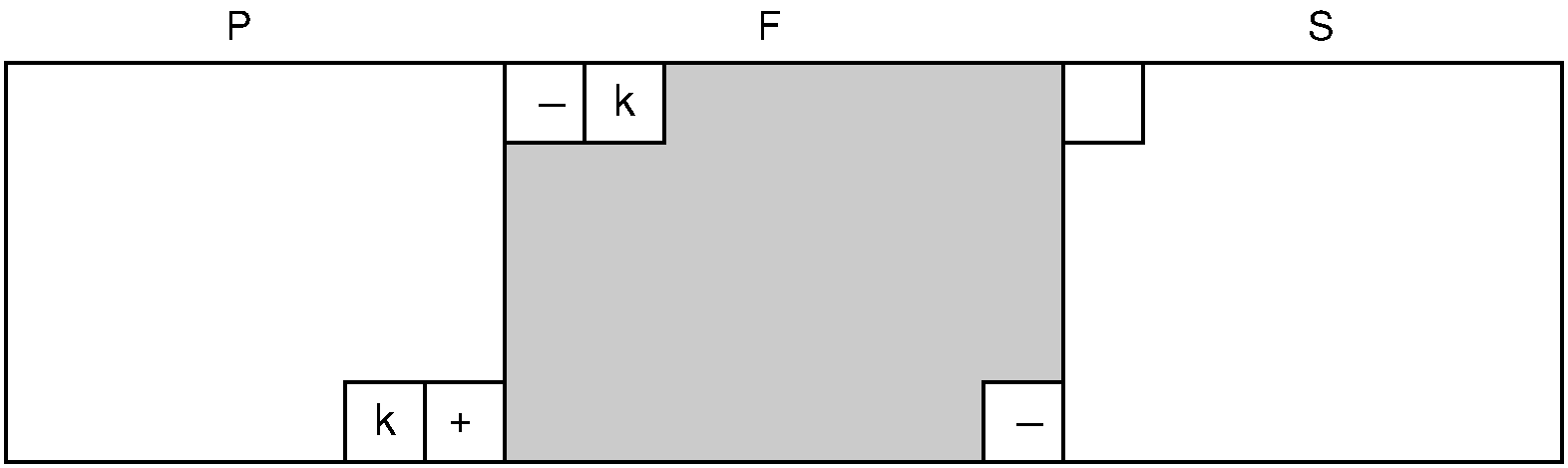

When a block \(F\) is freed, it must be merged into the freelist. If we do not care about merging adjacent free blocks, then this is a simple insertion into the doubly linked list of free blocks. However, we would like to merge adjacent blocks, because this allows the memory manager to serve requests of the largest possible size. Merging is easily done due to the tag and size fields stored at the ends of each block, as illustrated by the figure below. Here, the memory manager first checks the unit of memory immediately preceding block \(F\) to see if the preceding block (call it \(P\)) is also free. If it is, then the memory unit before \(P\) ‘s tag bit stores the size of \(P\), thus indicating the position for the beginning of the block in memory. \(P\) can then simply have its size extended to include block \(F\). If block \(P\) is not free, then we just add block \(F\) to the freelist. Finally, we also check the bit following the end of block \(F\). If this bit indicates that the following block (call it \(S\)) is free, then \(S\) is removed from the freelist and the size of \(F\) is extended appropriately.

Figure 11.3.2: Adding block \(F\) to the freelist. The word immediately preceding the start of \(F\) in the memory pool stores the tag bit of the preceding block \(P\). If \(P\) is free, merge \(F\) into \(P\). We find the end of \(F\) by using \(F\) ‘s size field. The word following the end of \(F\) is the tag field for block \(S\). If \(S\) is free, merge it into \(F\).¶

We now consider how a “suitable” free block is selected to service a memory request. To illustrate the process, assume that we have a memory pool with 200 units of storage. After some series of allocation requests and releases, we have reached a point where there are four free blocks on the freelist of sizes 25, 35, 32, and 45 (in that order). Assume that a request is made for 30 units of storage. For our examples, we ignore the overhead imposed for the tag, link, and size fields discussed above.