List Iteration¶

1. List Iteration¶

To understand how algorithms can manipulate large-scale real-world abstractions we need to understand the combination of two concepts:

lists - that hold the data elements to be manipulated, and

iteration - the algorithmic device to process the elements of the list.

The combination of these two concepts—what we will term “list iteration”—means repeating the same processing steps to each element of the list one element at a time.

In real life people create and use a variety of lists: shopping lists, bucket lists, and to-do lists, to name a few. These lists have two things in common:

the list contains several items of similar character (i.e., the shopping list contains things that can be found in a store, the to-do list has tasks that need to be done), and

there is some action that we want to take for each item on the list (i.e., purchase an item on the shopping list, do a task on the to-do list).

In a similar way, a computational list contains data items of the same type and list iteration is used to apply some computing actions to each item on the list.

List iteration is critical to algorithms that analyze abstractions having many—perhaps a very large number—of instances. Imagine computing the average household income using the U.S. Census data. The abstraction of a household contains information about the household’s income, but there are tens of millions of instances of this abstraction. List iteration is critical in this case because it allows the same steps to be repeated for each instance.

The idea of a list also helps us to begin answering an important pragmatic question: How do we get an abstraction “inside” a computer? To answer this questions we need to learn more about “data structures”. A data structure is a means of organizing data in a computer. We will learn two important data structures—lists now and dictionaries later. We will also see that these two data structures are building blocks in the sense that we can put these simple data structures together to form more complex data organizations—as complex as the real world phenomenon that we are dealing with.

1.1. Lists¶

A list is simply a sequence of individual elements of the same type

arranged one after the other.

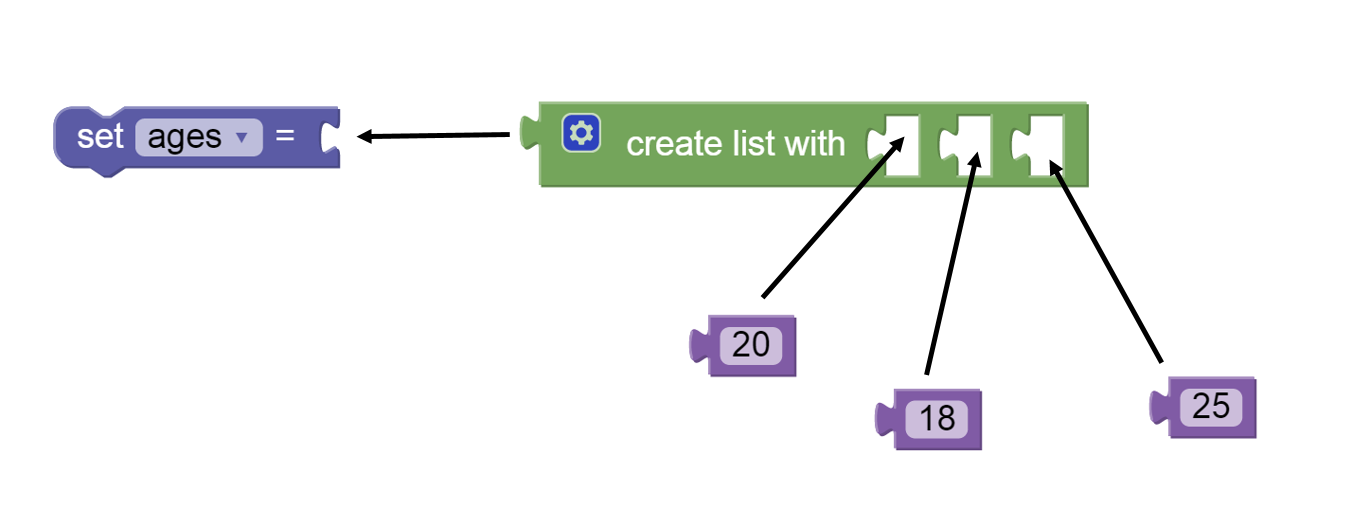

An example of a list in BlockPy is shown in the following figure.

The arrows in this figure show how the blocks would be assembled to

form a list of three numbers that is set as the value for a property.

The create list with block is found in the Lists menu.

The numbers are in the Values menu and the set block is in the

Property menu.

Figure 2: Creating a List¶

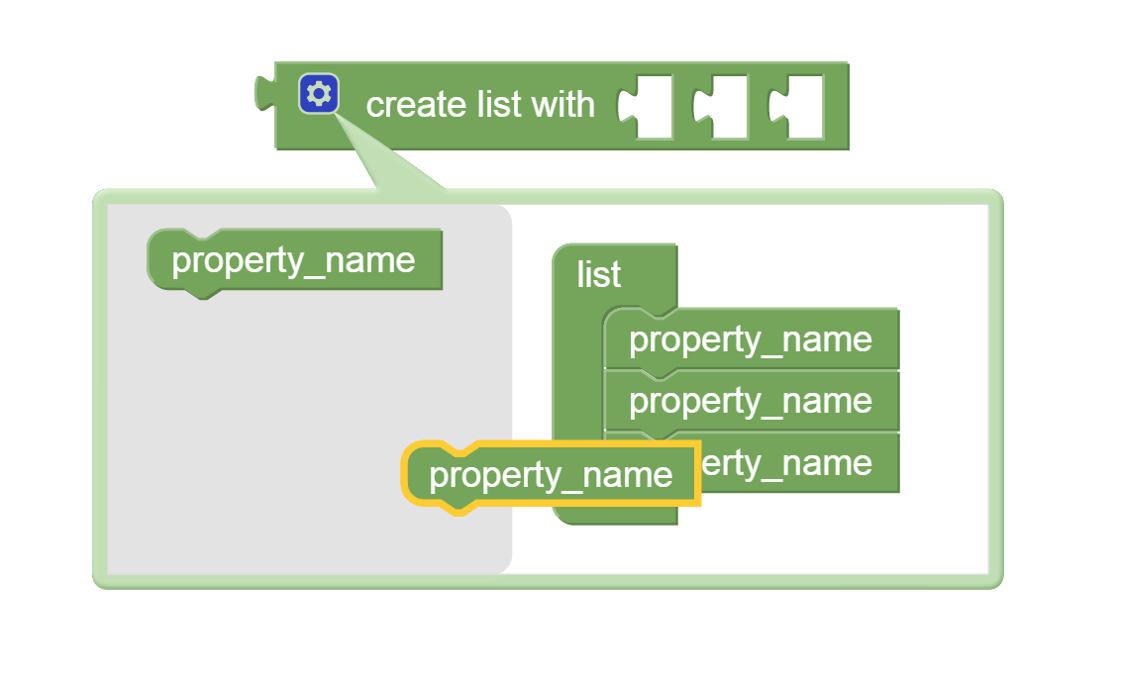

By default the create list with block creates a list with slots

for three elements.

Of course, a list with more or fewer slots for

elements may be needed.

For this reason the create list with block can be edited to add or

remove slots.

The figure below shows an example of the editing.

Figure 3: Editing the create list with block¶

To begin adding new list elements click on the blue colored gear

symbol in front of the word “create” on the create list with

block.

This pops up the editing menu shown in the left part of the figure

above.

The block labelled property_name can be dragged from the

gray area to the list grouping.

The left part of the above figure shows a highlighted property_name

block in the act of being dragged in this way.

When the property_name block is inserted into the list group

a new slot is added to the create list with block.

As many slots as needed can be added in this way by repeatedly

dragging a property_name block from the gray area to the list

group.

When done adding new list elements, click on the blue colored gear

symbol to collapse the editing menu.

To remove list elements begin by clicking on the blue colored gear

icon.

In the editing menu move a property_name block from the list

group to the gray area to its left.

This will shorten the list group and remove the corresponding slot

from the create list with block.

It is possible to view lists either in a text form or in a line plot

visualization.

Below is a live BlockPy canvas to illustrate both of these options.

In the BlockPy algorithm a list of four elements is created and set as

the value of the property number-list.

The number-list property is display as text using the print

block and then displayed as a line graph with the title

“List of Numbers”.

The blocks for printing and line graphing are found in the Output menu.

Run this program and observe the output displayed in the Printer

box (immediately above the BlockPy canvas).

Notice that the Printer box has a scroll bar and a control in the

lower right-hand corner for vertically resizing the display area.

Todo

- type: BlockPy

Put first BlockPy exercise here.

The text displayed by the print block is:

[2, 7, 10, 5]

where the square brackets surround the list and each item in the list is separated from the next item by a comma. This is the Python way of writing a list. By convention, the list is read from left to right, so the leftmost item is the first item in the list and the rightmost item is the last item in the list. In the example above, the number 2 is the first item and the number 5 is the last item.

The line graph similarly shows the four values in the list. Notice that the values are printed and plotted in left-to-right over in the list (i.e., 2 is the first number printed and plotted and 5 is the last number printed and plotted).

Work with the above canvas to:

add and remove elements from the list,

change the values of the numbers in the list,

change the title of the list, and

produce the plot before the printed output.

Resolve any questions or issues that you encounter in working with this simple list.

While the create list with block is a simple way to work with

small lists it is clearly too limited to deal with the long lists that

we would expect to see in a “big data” set.

We will see shortly a set of blocks that represent such “big data”

lists.

1.2. Iteration with Lists¶

In general, the concept of iteration means that a given set of steps are repeatedly performed until a stated goal is reached. For example, many of the maze algorithms repeated a set of steps (sensing the environment, turning and/or moving the avatar) until a stated goal (the maze exit) was reached.

List iteration is a form of iteration used when manipulating data organized in a list. The general form of list iteration is often expressed as:

- for each <element> in <some list>

do <these steps using element>

where the property “element” refers on each cycle of the iteration to a different element of the list. This property is often referred to as the iteration variable. The cycle is repeated for each item in the list. It is important to notice that the property “element” (the iteration variable) takes on a different value on each cycle of the iteration. This happens because on each cycle the property “element” refers to a different item on the list.

List iteration can be defined pragmatically as:

List iteration (pragmatic): performing a set of actions on each element in a list one element at a time.

Below is a BlockPy work space that has a simple algorithm illustrating list iteration. In this example we want to output each element of the list and identify which elements of the list are strictly greater than some threshold value, the value 5 in this case. In a more realistic situation we might use an algorithm like this to identify all earthquakes with the greatest magnitudes or all years when a crime rate is above some level.

Run the example algorithm and observe the output that it generates in the Printer area at the top of the workspace.

Todo

- type: BlockPy

Put second BlockPy exercise here.

This algorithm proceeds through four iterations as shown in the following table. Notice that on each iteration the value of the iteration variable changes. On each iteration the iteration variable has the same value as an item on the list.

The critical importance of iteration is that it works for lists of any length. Using the above work space add several more elements to the list and observe that the iteration without change works for this longer list.

1.3. The Iteration Variable and Initialization¶

The phrase “one element at a time” means that algorithms must be designed to deal with the fact that the steps of the iteration only have direct access to the value of the iteration variable (i.e., the value of the “current” list element). In some cases only the current value is needed. This was the case for the algorithm above to identify whether each list element was above a threshold. However, when the algorithms needs to know something about an element that it saw earlier then the algorithm must “remember” that fact in its state. eing able to define the algorithm’s state to accommodate this aspect of iteration is an important skill.

Consider an algorithm to find the maximum value in a list of numbers that are all greater than zero. An algorithm like this is useful to answer questions like: What is the largest magnitude earthquake? or What is the highest crime rate? With list iteration the entire list is not visible at once—all we can “see” is that list value revealed by the iteration variable. For example, on the second iteration the list that is [2, 7, 10, 5] would appear as [–, 7, –, –, …]. The first number in the list (the one seen on the first iteration) is no longer visible and the numbers that follow the current number (the number 7) are have not yet been seen.

So how is it possible to find the maximum value if we can only see one number at a time? The algorithm needs an additional property to help remember what it has seen so far in the iteration. Because we are trying to find the maximum, this additional property simply needs to record a single number: the largest number seen so far. Examine the algorithm in the following workspace to see how this works.

Todo

- type: BlockPy

Put third BlockPy exercise here.

For the example list the algorithm proceeds through four iterations as shown in the following table.

The property maximum records the largest value seen in the list so far. Trace through the algorithm and convince yourself that this table is correct.

An important aspect of this (and many similar) iteration algorithms is

the need for initialization.

The first row in the table shows that the property maximum is

given the value zero before the iteration is begun.

This can be seen in the Blockly algorithm.

Giving the property maximum this initial value is called

initialization.

This initialization is necessary so that on the first iteration the

comparison of the iteration variable (the property item) with the

property maximum makes sense.

Without the initialization of maximum there is no way of telling

whether the comparison is true or false because we do not know what

value the property maximum has—clearly not the way we want

to write a good algorithm.

Try removing or disabling the block that initializes the maximum

property and observe what happens when you run the algorithm.

1.4. Lists, Iteration, Big Data, and Abstraction¶

The fact that iteration can work with lists of any length connects naturally to the world of “big data” because a “big data” list is simply a list that has a very large number of items. This ability of iteration to apply to any number of items the same set of actions gives computing its “power”. Many machines generate physical power by performing a mechanical action repetitively: the repetitive motion of the pistons in an internal combustion engine generates the physical power needed to move a vehicle. By analogy, the repetitive processing of list items by an algorithm using iteration generates the information processing power needed to answer questions about a large collection of data.

The ideas of lists and iteration are also connected to the larger concept of abstraction. We have drawn an abstraction as a table. Each row of the table is an instance of some real world entity that is being modeled by the abstraction. The collection of instances can be organized as a list—each element of the list is an instance. To manipulate the abstraction iteration can be used to repetitively process each element of the list (i.e., each instance).

This leads to a conceptual definition of list iteration as:

List iteration (conceptual): performing a set of actions on each instance of an abstraction one instance at a time.

To fully realize this idea of processing an abstraction we will need to learn a bit more—but not much more.