5.1. Basic Pointers¶

5.1.1. What is a pointer?¶

There's a lot of nice, tidy code you can write without knowing about pointers. But once you learn to use the power of pointers, you can never go back. There are too many things that can only be done with pointers. But with increased power comes increased responsibility. Pointers allow new and more ugly types of bugs, and pointer bugs can crash in random ways which makes them more difficult to debug. Nonetheless, even with their problems, pointers are an irresistibly powerful programming construct. (The following explanation uses the C language syntax where a syntax is required; there is a discussion of Java at the section.)

Pointers solve two common software problems. First, pointers allow different sections of code to share information easily. You can get the same effect by copying information back and forth, but pointers solve the problem better. Second, pointers enable complex linked data structures like linked lists and binary trees.

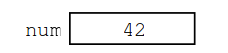

Simple int and float variables operate pretty intuitively. An

int variable is like a box which can store a single int value such

as 42. In a drawing, a simple variable is a box with its current value

drawn inside.

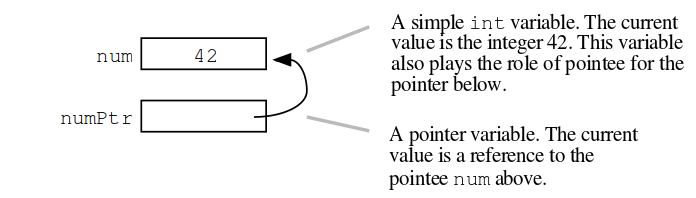

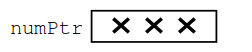

A pointer works a little differently, it does not store a simple value directly. Instead, a pointer stores a reference to another value. The variable the pointer refers to is sometimes known as its pointee. In a drawing, a pointer is a box which contains the beginning of an arrow which leads to its pointee. (There is no single, official, word for the concept of a pointee—pointee is just the word used in these explanations.)

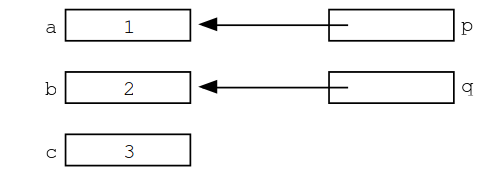

The following drawing shows two variables: num and numPtr. The simple variable num

contains the value 42 in the usual way. The variable numPtr is a pointer which contains

a reference to the variable num. The numPtr variable is the pointer and num is its

pointee. What is stored inside of numPtr? Its value is not an int. Its value is a

reference to an int.

5.1.2. Pointer Reference and Dereference¶

The dereference operation follows a pointer's reference to get

the value of its pointee.

The value of the dereference of numPtr above is 42. When the dereference operation is

used correctly, it's simple. It just accesses the value of the pointee. The only restriction is

that the pointer must have a pointee for the dereference to access. Almost all bugs in

pointer code involve violating that one restriction. A pointer must be assigned a pointee

before dereference operations will work.

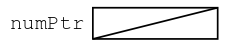

The constant NULL is a special pointer value which encodes the idea of "points to nothing". It turns out to be convenient to have a well defined pointer value which represents the idea that a pointer does not have a pointee. It is a runtime error to dereference a NULL pointer. In drawings, the value NULL is usually drawn as a diagonal line between the corners of the pointer variable's box.

The C language uses the symbol NULL for this purpose. NULL is equal to the integer constant 0, so NULL can play the role of a boolean false. Official C++ no longer uses the NULL symbolic constant—use the integer constant 0 directly. Java uses the symbol null.

5.1.3. Pointer Assignment¶

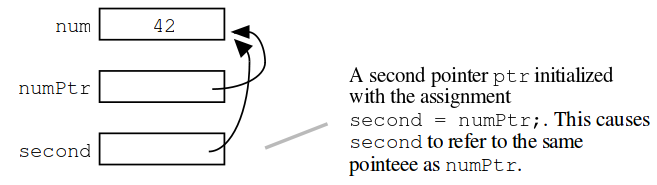

The assignment operation (=) between two pointers makes them point to the same

pointee. It's a simple rule for a potentially complex situation, so it is worth repeating:

assigning one pointer to another makes them point to the same thing. The example below

adds a second pointer, second, assigned with the statement second = numPtr;.

The result is that second points to the same pointee as numPtr. In the drawing, this

means that the second and numPtr boxes both contain arrows pointing to num.

Assignment between pointers does not change or even touch the pointees. It just changes

which pointee a pointer refers to.

After assignment, the == test comparing the two pointers will return true. For example

(second==numPtr) above is true. The assignment operation also works with the

NULL value. An assignment operation with a NULL pointer copies the NULL value

from one pointer to another.

Memory drawings are the key to thinking about pointer code. When you are looking at code, thinking about how it will use memory at run time, then make a quick drawing to work out your ideas. This tutorial certainly uses drawings to show how pointers work. That's the way to do it.

5.1.3.1. Sharing¶

Two pointers which both refer to a single pointee are said to be "sharing". That two or more entities can cooperatively share a single memory structure is a key advantage of pointers in all computer languages. Pointer manipulation is just technique—sharing is often the real goal. Later we will see how sharing can be used to provide efficient communication between parts of a program.

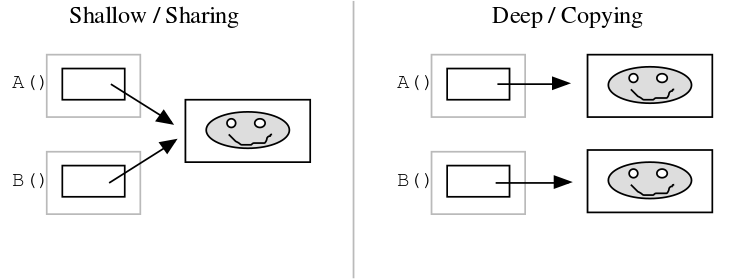

5.1.3.2. Shallow and Deep Copying¶

In particular, sharing can enable communication between two functions. One function passes a pointer to the value of interest to another function. Both functions can access the value of interest, but the value of interest itself is not copied. This communication is called shallow copy since instead of making and sending a (large) copy of the value of interest, a (small) pointer is sent and the value of interest is shared. The recipient needs to understand that they have a shallow copy, so they know not to change or delete it since it is shared. The alternative where a complete copy is made and sent is known as a deep copy. Deep copies are simpler in a way, since each function can change their copy without interfering with the other copy, but deep copies run slower because of all the copying. The drawing below shows shallow and deep copying between two functions, A() and B(). In the shallow case, the smiley face is shared by passing a pointer between the two. In the deep case, the smiley face is copied, and each function gets their own.

The next module will explain the above sharing technique in detail.

5.1.4. Bad Pointers¶

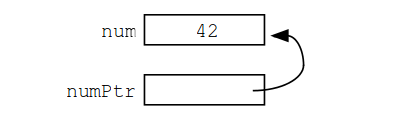

When a pointer is first allocated, it does not have a pointee. The pointer is uninitialized or simply "bad". A dereference operation on a bad pointer is a serious runtime error. If you are lucky, the dereference operation will crash or halt immediately (Java behaves this way). If you are unlucky, the bad pointer dereference will corrupt a random area of memory, slightly altering the operation of the program so that it goes wrong some indefinite time later. Each pointer must be assigned a pointee before it can support dereference operations. Before that, the pointer is bad and must not be used. In our memory drawings, the bad pointer value is shown with an XXX value.

Bad pointers are very common. In fact, every pointer starts out with a bad value. Correct code overwrites the bad value with a correct reference to a pointee, and thereafter the pointer works fine. There is nothing automatic that gives a pointer a valid pointee.

Quite the opposite—most languages make it easy to omit this important step. You just have to program carefully. If your code is crashing, a bad pointer should be your first suspicion. Pointers in dynamic languages such as Perl, LISP, and Java work a little differently. The run-time system sets each pointer to NULL when it is allocated and checks it each time it is dereferenced. So code can still exhibit pointer bugs, but they will halt politely on the offending line instead of crashing haphazardly like C. As a result, it is much easier to locate and fix pointer bugs in dynamic languages. The run-time checks are also a reason why such languages always run at least a little slower than a compiled language like C or C++.

One way to think about pointer code is that operates at two levels—pointer level and pointee level. The trick is that both levels need to be initialized and connected for things to work. (1) the pointer must be allocated, (1) the pointee must be allocated, and (3) the pointer must be assigned to point to the pointee. It's rare to forget step (1). But forget (2) or (3), and the whole thing will blow up at the first dereference. Remember to account for both levels—make a memory drawing during your design to make sure it's right.

5.1.5. Syntax¶

The above basic features of pointers, pointees, dereferencing, and assigning are the only concepts you need to build pointer code. However, in order to talk about pointer code, we need to use a known syntax which is about as interesting as... a syntax. We will use the Java language syntax which has the advantage that it has influenced the syntaxes of several languages.

5.1.5.1. Pointer Type Syntax¶

A pointer type in C is just the pointee type followed by an asterisk (*).

int* type: pointer to int

float* type: pointer to float

struct fraction* type: pointer to struct fraction

struct fraction** type: pointer to struct fraction*

5.1.5.2. Pointer Variables¶

Pointer variables are declared just like any other variable. The declaration gives the type and name of the new variable and reserves memory to hold its value. The declaration does not assign a pointee for the pointer—the pointer starts out with a bad value.

int* numPtr; // Declare the int* (pointer to int) variable numPtr.

// This allocates space for the pointer, but not the pointee.

// The pointer starts out "bad"

5.1.5.3. The & Operator—Reference To¶

There are several ways to compute a reference to a pointee suitable

for storing in a pointer.

The simplest way is the & operator.

The & operator can go to the left of any variable,

and it computes a reference to that variable.

The code below uses a pointer and

an & to produce the earlier num/numPtr example.

void NumPtrExample() {

int num;

int* numPtr;

num = 42;

numPtr = #

// Compute a reference to num, and store it in numPtr

// At this point, memory looks like drawing above

}

It is possible to use & in a way which compiles fine but which creates problems at run time. The full discussion of how to correctly use & is in the next module. For now we will just use & in a simple way.

5.1.5.4. The * Operator—Dereference¶

The star operator (*) dereferences a pointer. The * is a unary operator which goes to the left of the pointer it dereferences. The pointer must have a pointee, or it's a runtime error.

5.1.6. Example Pointer Code¶

With the syntax defined, we can now write some pointer code that demonstrates all the pointer rules.

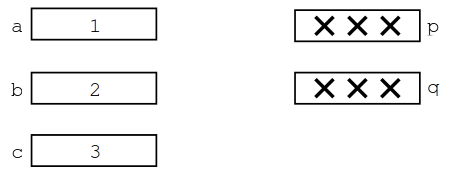

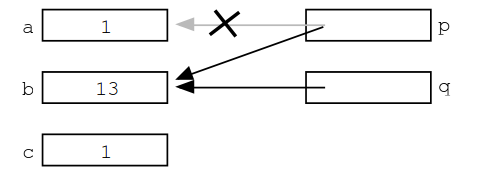

void PointerTest() {

// allocate three integers and two pointers

int a = 1;

int b = 2;

int c = 3;

int* p;

int* q;

// Here is the state of memory at this point.

// T1 -- Notice that the pointers start out bad.

p = &a;

// set p to refer to a

q = &b;

// set q to refer to b

// T2 -- The pointers now have pointees

// Now we mix things up a bit

c = *p;

// retrieve p's pointee value (1) and put it in c

p = q;

// change p to share with q (p's pointee is now b)

*p = 13;

// dereference p to set its pointee (b) to 13 (*q is now 13)

// T3 -- Dereferences and assignments mix things up

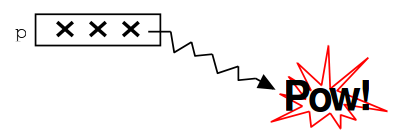

5.1.6.1. Bad Pointer Example¶

Code with the most common sort of pointer bug will look like the above correct code, but without the middle step where the pointers are assigned pointees. The bad code will compile fine, but at run-time, each dereference with a bad pointer will corrupt memory in some way. The program will crash sooner or later. It is up to the programmer to ensure that each pointer is assigned a pointee before it is used. The following example shows a simple example of the bad code and a drawing of how memory is likely to react.

void BadPointer() {

int* p;

// allocate the pointer, but not the pointee

*p = 42;

// this dereference is a serious runtime error

}

// What happens at runtime when the bad pointer is dereferenced?

5.1.7. Pointer Rules Summary¶

No matter how complex a pointer structure gets, the list of rules remains short.

- A pointer stores a reference to its pointee. The pointee, in turn, stores something useful.

- The dereference operation on a pointer accesses its pointee. A pointer may only be dereferenced after it has been assigned to refer to a pointee. Most pointer bugs involve violating this one rule.

- Allocating a pointer does not automatically assign it to refer to a pointee. Assigning the pointer to refer to a specific pointee is a separate operation which is easy to forget.

- Assignment between two pointers makes them refer to the same pointee which introduces sharing.

5.1.8. How Do Pointers Work In Java?¶

Java has pointers, but they are not manipulated with explicit operators such as * and &.

In Java, simple data types such as int and char operate just as in C. More complex types

such as arrays and objects are automatically implemented using pointers. The language

automatically uses pointers behind the scenes for such complex types, and no pointer

specific syntax is required. The programmer just needs to realize that operations like

a=b; will automatically be implemented with pointers if a and b are arrays or objects. Or

put another way, the programmer needs to remember that assignments and parameters

with arrays and objects are intrinsically shallow or shared—see the Deep vs. Shallow

material above. The following code shows some Java object references. Notice that there

are no *'s or &'s in the code to create pointers. The code

intrinsically uses pointers.

Also, the garbage collector takes care of the deallocation

automatically at the end of the function.

public void JavaShallow() {

Foo a = new Foo();

// Create a Foo object (no * in the declaration)

Foo b = new Foo();

// Create another Foo object

b=a;

// This is automatically a shallow assignment --

// a and b now refer to the same object.

a.Bar();

// This could just as well be written b.Bar();

// There is no memory leak here -- the garbage collector

// will automatically recycle the memory for the two objects.

}

The Java approach has two main features.

- Fewer bugs. Because the language implements the pointer manipulation accurately and automatically, the most common pointer bug are no longer possible, Yay! Also, the Java runtime system checks each pointer value every time it is used, so NULL pointer dereferences are caught immediately on the line where they occur. This can make a programmer much more productive.

- Slower. Because the language takes responsibility for implementing so much pointer machinery at runtime, Java code runs slower than the equivalent C code. (There are other reasons for Java to run slowly as well. There is active research in making Java faser in interesting ways—the Sun "Hot Spot" project.) In any case, the appeal of increased programmer efficiency and fewer bugs makes the slowness worthwhile for some applications.

5.1.9. How Are Pointers Implemented In The Machine?¶

How are pointers implemented?

The short explanation is that every area of memory in the

machine has a numeric address like 1000 or 20452.

A pointer to an area of memory is really just an integer which is

storing the address of that area of memory. The dereference

operation looks at the address, and goes to that area of memory to retrieve the pointee

stored there. Pointer assignment just copies the numeric address from one pointer to

another. The NULL value is generally just the numeric address 0—the computer just

never allocates a pointee at 0 so that address can be used to represent NULL. A bad

pointer is really just a pointer which contains a random address—just like an

uninitialized int variable which starts out with a random int value. The pointer has not

yet been assigned the specific address of a valid pointee. This is why dereference operations with bad pointers are so unpredictable. They operate on whatever random area

of memory they happen to have the address of.

5.1.10. The Term 'Reference'¶

The word reference means almost the same thing as the word "pointer". The difference is that "reference" tends to be used in a discussion of pointer issues which is not specific to any particular language or implementation. The word "pointer" connotes the common C/C++ implementation of pointers as addresses. The word "reference" is also used in the phrase reference parameter which is a technique that uses pointer parameters for two-way communication between functions. This technique is the subject of a later module.

5.1.11. Why Are Bad Pointer Bugs So Common?¶

Why is it so often the case that programmers will allocate a pointer,

but forget to set it to refer to a pointee?

The rules for pointers don't seem that complex, yet every programmer

makes this error repeatedly.

Why?

The problem is that we are trained by the tools we use.

Simple variables don't require any extra setup.

You can allocate a simple variable, such as int

, and use it immediately. All that int, char, struct fraction code you have written has trained you, quite reasonably,

that a variable may be used once it is declared. Unfortunately, pointers look like simple variables but they require the extra initialization

before use. It's unfortunate, in a way, that pointers happen look like other variables, since

it makes it easy to forget that the rules for their use are very different. Oh well. Try to

remember to assign your pointers to refer to pointees. Don't be surprised when you forget.