5.11. Implementing Recursion¶

WARNING! You should not read this section unless you are already comfortable with implementing recursive functions. One of the biggest hang-ups for students learning recursion is too much focus on the recursive “process”. The right way to think about recursion is to just think about the return value that the recursive call gives back. Thinking about how that answer is computed just gets in the way of understanding. There are good reasons to understand how recursion is implemented, but helping you to write recursive functions is not one of them.

Perhaps the most common computer application that uses stacks is not even visible to its users. This is the implementation of subroutine calls in most programming language runtime environments. A subroutine call is normally implemented by pushing necessary information about the subroutine (including the return address, parameters, and local variables) onto a stack. This information is called an activation record. Further subroutine calls add to the stack. Each return from a subroutine pops the top activation record off the stack. As an example, here is a recursive implementation for the factorial function.

// Recursively compute and return n!

static long rfact(int n) {

// fact(20) is the largest value that fits in a long

if ((n < 0) || (n > 20)) { return -1; }

if (n <= 1) { return 1; } // Base case: return base solution

return n * rfact(n-1); // Recursive call for n > 1

}

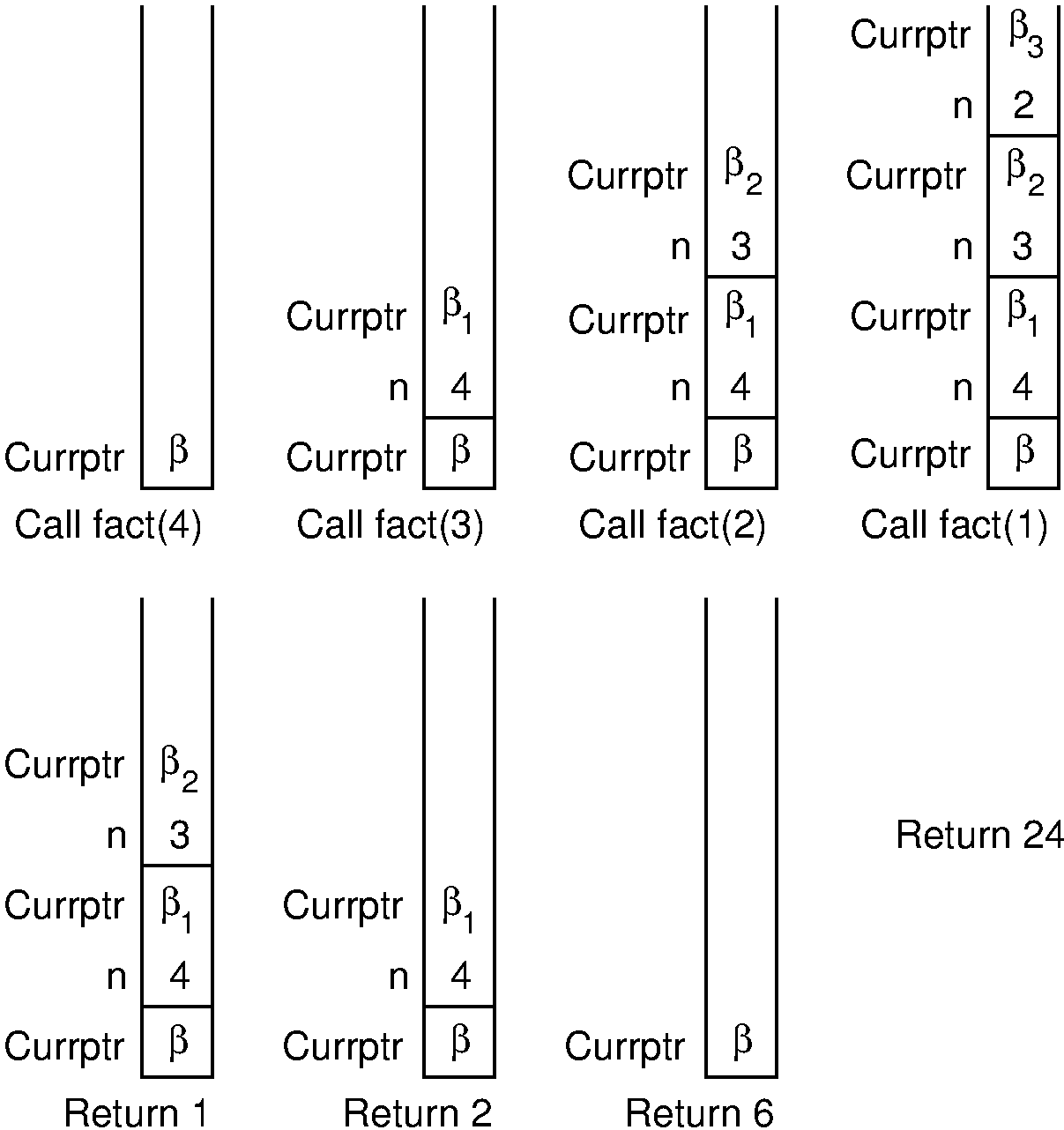

Here is an illustration for how the internal processing works.

\(\beta\) values indicate the address of the program instruction

to return to after completing the current function call.

On each recursive function call to fact, both the return

address and the current value of n must be saved.

Each return from fact pops the top activation record off the

stack.

Consider what happens when we call fact with the value 4.

We use \(\beta\) to indicate the address of the program

instruction where the call to fact is made.

Thus, the stack must first store the address \(\beta\), and the

value 4 is passed to fact.

Next, a recursive call to fact is made, this time with value 3.

We will name the program address from which the call is

made \(\beta_1\).

The address \(\beta_1\), along with the current value for

\(n\) (which is 4), is saved on the stack.

Function fact is invoked with input parameter 3.

In similar manner, another recursive call is made with input parameter 2, requiring that the address from which the call is made (say \(\beta_2\)) and the current value for \(n\) (which is 3) are stored on the stack. A final recursive call with input parameter 1 is made, requiring that the stack store the calling address (say \(\beta_3\)) and current value (which is 2).

At this point, we have reached the base case for fact, and so

the recursion begins to unwind.

Each return from fact involves popping the stored value for

\(n\) from the stack, along with the return address from the

function call.

The return value for fact is multiplied by the restored value

for \(n\), and the result is returned.

Because an activation record must be created and placed onto the stack for each subroutine call, making subroutine calls is a relatively expensive operation. While recursion is often used to make implementation easy and clear, sometimes you might want to eliminate the overhead imposed by the recursive function calls. In some cases, such as the factorial function above, recursion can easily be replaced by iteration.

Example 5.11.1

As a simple example of replacing recursion with a stack, consider the following non-recursive version of the factorial function.

// Return n!

static long sfact(int n) {

// fact(20) is the largest value that fits in a long

if ((n < 0) || (n > 20)) { return -1; }

// Make a stack just big enough

Stack S = new AStack(n);

while (n > 1) { S.push(n--); }

long result = 1;

while (S.length() > 0) {

result = result * (Integer)S.pop();

}

return result;

}

Here, we simply push successively smaller values of \(n\) onto the stack until the base case is reached, then repeatedly pop off the stored values and multiply them into the result.

An iterative form of the factorial function is both simpler and faster than the version shown in the example. But it is not always possible to replace recursion with iteration. Recursion, or some imitation of it, is necessary when implementing algorithms that require multiple branching such as in the Towers of Hanoi algorithm, or when traversing a binary tree. The Mergesort and Quicksort sorting algorithms also require recursion. Fortunately, it is always possible to imitate recursion with a stack. Let us now turn to a non-recursive version of the Towers of Hanoi function, which cannot be done iteratively.

Example 5.11.2

Here is a recursive implementation for Towers of Hanoi.

// Compute the moves to solve a Tower of Hanoi puzzle.

// Function move does (or prints) the actual move of a disk

// from one pole to another.

// n: The number of disks

// start: The start pole

// goal: The goal pole

// temp: The other pole

static void TOHr(int n, Pole start, Pole goal, Pole temp) {

if (n == 0) { return; } // Base case

TOHr(n-1, start, temp, goal); // Recursive call: n-1 rings

move(start, goal); // Move bottom disk to goal

TOHr(n-1, temp, goal, start); // Recursive call: n-1 rings

}

TOH makes two recursive calls:

one to move \(n-1\) rings off the bottom ring, and another to

move these \(n-1\) rings back to the goal pole.

We can eliminate the recursion by using a stack to store a

representation of the three operations that TOH must perform:

two recursive calls and a move operation.

To do so, we must first come up with a representation of the

various operations, implemented as a class whose objects will be

stored on the stack.

static class TOHobj {

int op;

int num;

Pole start, goal, temp;

// Recursive call operation

TOHobj(int o, int n, Pole s, Pole g, Pole t)

{ op = o; num = n; start = s; goal = g; temp = t; }

// MOVE operation

TOHobj(int o, Pole s, Pole g)

{ op = o; start = s; goal = g; }

}

static void TOHs(int n, Pole start, Pole goal, Pole temp) {

// Make a stack just big enough

Stack S = new AStack(2*n+1);

S.push(new TOHobj(TOH, n, start, goal, temp));

while (S.length() > 0) {

TOHobj it = (TOHobj)S.pop(); // Get next task

if (it.op == MOVE) { // Do a move

move(it.start, it.goal);

}

else if (it.num > 0) { // Imitate TOH recursive solution (in reverse)

S.push(new TOHobj(TOH, it.num-1, it.temp, it.goal, it.start));

S.push(new TOHobj(MOVE, it.start, it.goal)); // A move to do

S.push(new TOHobj(TOH, it.num-1, it.start, it.temp, it.goal));

}

}

}

We first enumerate the possible operations MOVE and TOH, to

indicate calls to the move function

and recursive calls to TOH, respectively.

Class TOHobj stores five values: an operation value

(indicating either a MOVE or a new TOH operation), the number of

rings, and the three poles.

Note that the move operation actually needs only to store

information about two poles.

Thus, there are two constructors: one to store the state when

imitating a recursive call, and one to store the state for a move

operation.

An array-based stack is used because we know that the stack

will need to store exactly \(2n+1\) elements.

The new version of TOH begins by placing on the stack a

description of the initial problem for \(n\) rings.

The rest of the function is simply a while loop that pops the

stack and executes the appropriate operation.

In the case of a TOH operation (for \(n>0\)), we store on

the stack representations for the three operations executed by the

recursive version.

However, these operations must be placed on the stack in reverse

order, so that they will be popped off in the correct order.

Recursive algorithms lend themselves to efficient implementation with a stack when the amount of information needed to describe a sub-problem is small. For example, Quicksort can effectively use a stack to replace its recursion since only bounds information for the subarray to be processed needs to be saved.