4.3. Grouping Objects Using Lists and Nested For Loops¶

4.3.1. Collections of Objects¶

While we have been using individual variables or fields to refer to individual objects, eventually you will need to work with programs that manage many more than just one or two objects. When you are working with a large number of objects, placing each one in a separate variable or field is cumbersome, and eventually makes the code more complicated and bloated. Instead, when working with larger amounts of data, we see the need for container objects that allow us to hold and manage collections of objects.

Java provides a library of utility classes that help with many common

tasks, and this library includes several Collection classes. These

come in three broad categories that are common in many programming

languages:

Lists allow us to store a sequence of values in order.

Sets allow us to store an unordered collection of values.

Maps allow us to store lookup tables that allow us to use one piece of data to look up another piece of data associated with it, like using a word to look up its definition in a dictionary. Besides the word map, they also are often called dictionaries, associative arrays, or hashes.

Collections group objects together. All of these collections share a number of properties:

They increase their capacity as necessary to hold as much data as needed.

They keep a count of the number of values they hold.

They keep those values organized internally, allowing us to add or remove them when we want.

The details of how all this is done are hidden. Actually, we don’t need to know how the internals work in order to use a collection. Instead, we rely on the collection to do its job for us.

4.3.2. Interfaces¶

Because there are times when we want to know how to use a class without caring about its internal details, it would be nice to talk only about the services (or methods) a class provides. Java provides a tool for us to describe the set of methods provided by a class without being concerned about its internal implementation called an interface. An interface is similar to a class, but only lists the declarations of the public methods in the class (and any public constants you wish to provide). It does not include the fields, constructors, method implementations or any private aspects–just the public parts of the declarations that allow you to use it.

Compared to a class, an interface provides just enough information for you to be able to call the public methods and use it, while a class provides the full detail of exactly how those methods are actually implemented. As a result, you can use a class to create an object, since you have the full implementation available. However, you cannot use an interface by itself to create an object–all objects belong to some class, and an interface only describes a set of method declarations that a class might provide.

Why would we use an interface? Interfaces are used for three main reasons in programming:

By separating the declarations of the methods into an interface, and then moving the implementation to a separate class, it becomes possible for the same interface to be implemented in multiple different ways using different strategies. Multiple implementations is tricky and error-prone without interfaces, but since any number of classes can implement an interface just by providing the required methods, they are useful when there are multiple techniques for implementing the same algorithm or data structure.

Through an interface, you can capture a common set of methods that you expect to appear in multiple classes so that you can give the set of methods a name and ensure that classes providing that set of methods all do it consistently.

By separating the declarations of the methods into an interface, you enable programmers who need to use the code to build on top of the interface, in parallel with other programmers who are writing what is underneath. Interfaces can allow groups to communicate and depend on each other, even if the underlying software isn’t implemented yet.

As an example, suppose we were working on a program that manages graphical

shapes and we wanted all of the various types of graphical shapes to be

drawable on the screen. We might do this by imagining that each shape

would have a draw() method that would draw it on the screen. We could

capture that in an interface like this:

public interface Drawable

{

public void draw();

}

You’ll notice a few things here that are different from other Java code

we’ve seen. For one thing, instead of saying public class we see the

keyword interface used. For another, our method signature is followed

by a ;, not curly braces. There is no implementation for the method

at all–that is left up to the individual classes that provide this method.

The interface only declares the method name, parameters, and return type.

The more general syntax for writing an interface looks like this:

public interface InterfaceName

{

// any number of constant values

// any number of method signatures WITHOUT implementation.

}

By itself, this code won’t do anything. However, it captures the dea

of providing a single draw() method. We cannot use it to create

objects–we need a class for that. Any class we write that we intend

to conform to this interface should implement it:

public class Rectangle

implements Drawable

{

// ...

public void draw()

{

// ...

}

}

public class Circle

implements Drawable

{

// ...

public void draw()

{

// ...

}

}

In these two class definitions, we use the keyword implements followed

by the interface name to declare that the class provides all the methods

included in that interface. When we say class Rectangle implements Drawable we are

claiming that the class Rectangle provides all the methods declared in

the interface Drawable. Further, this is a guarantee, and we will receive

a compiler error if we accidentally misspell the name of draw() or

declare it in a way that is inconsistent with the way it is declared

in Drawable.

The Rectangle class will

not compile until we implement a method with the

signature public void draw().

We can add any other fields or methods we want, but that draw()

method must be implemented.

However, by declaring that class Rectangle implements Drawable, now

any and all programmers (or source code) that use the Rectangle class

will know that it provides a draw() method, and that this method can be

used the same way it can for any other drawable objects.

By itself, this can seem like something of an odd structure in a language. Couldn’t a developer just remember to implement that one method? In our example, probably. But interfaces provide a way for us to explicitly write these requirements down so we can share them, and also provides a mechanism for the compiler to check that we have included the required methods with the correct declarations, and warn us of any mistakes we might make in that regard. So interfaces give better error checking and better communication between programmers.

4.3.3. Check Your Understanding: Interfaces¶

4.3.4. Syntax Practice 8a: Strings¶

4.3.5. The List Interface¶

Previously, we’ve worked on saving specific pieces of data to variables. For example, suppose we were working on a list of names stored as strings–think in terms of the names of all your classmates. We could store each name in a separate variable.

String name01 = "Anna";

String name02 = "Joey";

String name03 = "Maria";

String name04 = "Chris";

However, this becomes pretty tedious and inefficient pretty quickly when you are working with many names. For example, if you have 100 names to work with, you will need 100 different variables. Now think about how you would print them all out. You would need a separate statement for each variable, so it would also take 100 lines of code to print out all of the names.

Instead, there’s another way we can store many values. Instead of placing

each value in a separate variable, we can use one variable that acts like

a big container, and drop each individual name into the container.

Java uses the term Collection for objects that act like containers to

hold groups of other objects. In fact, Collection is actually an

interface in Java that defines the common methods that all container

objects provide. By the way, containers are often called data structures,

because they organize a group of data values in a structured way to solve

particular types of problems.

For now, we are going to focus on one specific group of containers: lists.

In Java, List is yet another interface that defines all of the methods

common to different kinds of lists. Java provides multiple classes that

store sequences of items in different ways: some are more focused on

providing faster access to individual objects by specifying their position

in line, and others are more focused on providing faster insertion and removal

operations. But there is a tradeoff, since most containers can make some of

the operations faster at the expense of slowing down others. Using a

common interface allows programmers to treat these different implementations

as completely interchangeable in terms of how methods are used, even if

some methods may run faster or slower depending on the specific class

underneath.

The following table summarizes the most common List methods:

Method Name |

Purpose |

|---|---|

|

adds an item to the list |

|

returns the item stored at this index |

|

sets the item at some index to be some value |

|

removes all elements from the list |

|

returns |

|

removes element at the specified index from the list |

|

returns the number of elements in the list |

|

returns |

|

inserts an item into the list at the specified position, moving other items back by one to make room |

4.3.6. Generics¶

The List interface also marks our first encounter with generic types

in Java. The List interface is generic, meaning that it requires us

to specify another type that it works with. We do this by providing another

type as a parameter whenever we use the List interface name. For

List, the other type represents the type of objects that the list will

hold.

List<String> names = ...;

names.add("Sara"); // works, since value is a String

names.add(new Jeroo()); // compiler error, since it is not a String

List<Jeroo> jeroos = ...;

jeroos.add("Sara"); // compiler error, since it is not a Jeroo

jeroos.add(new Jeroo()); // works, since value is a Jeroo

A generic type is a class or interface that requires one or more other

types as parameters. We specify those other types inside angle

brackets (<…>). Remember that you always must specify the types each

time you are declaring a field, variable, parameter, or return type. For

example, when using List you should always provide the type so

that it is clear what kind of items go into the list.

4.3.7. ArrayList¶

Remember that because List is an interface, it does not provide any

information to create an object–it only specifies the required methods.

To create an actual object, you need a class that implements the interface–often

called a concrete class, because it provides the concrete implementation

details of how all fields are initialized and how all methods behave internally.

While there are multiple implementations of the List interface, in this

course we will rely on the one that is used most commonly: ArrayList.

Because ArrayList implements List, you know it provides all of the

methods described in the previous section. ArrayList is also a generic

type, and takes a parameter in angle brackets (<…>) to indicate the type

of items that go in the list.

Take a few minutes to watch the following video:

In an ArrayList, data are arranged in a linear or sequential

structure, with one element following another.

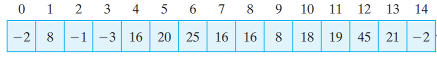

For example, if we had an ArrayList` of integers, it might look like this:

The large numbers inside the boxes are the elements of the ArrayList. The

small numbers outside the boxes are the indexes (or indices, or positions)

used to identify each location in the ArrayList. Notice that the index of

the first element is 0, not 1. It’s important to remember that, much like

Pixels in a picture, ArrayList

indexing starts at 0 instead of 1. Forgetting this fact is an easy mistake

to make.

4.3.7.1. Programming with ArrayLists¶

Lets try re-creating the image above as an ArrayList in code.

4.3.7.1.1. Adding an Import¶

Before we can start though, we need to add an import statement to our code:

import java.util.*;

Without this, java will not recognize the names List or ArrayList.

4.3.7.1.2. Declaring and Instantiating an ArrayList¶

Since the List interface tells us everything we need to know about all

the methods available on lists, we can use it to declare a variable like this

(remember to include the type of elements inside angle brackets):

List<Integer> list = ...;

However, we cannot use new with an interface name like List. We can only

use new with the name of a class, since new creates a new object by

using the class as a template. Interfaces cannot be used in this way. So

instead, when we use new, we can use ArrayList as the name of the

specific implementation class we want to instantiate.

List<Integer> list = new ArrayList<Integer>();

Remember that when we say <Integer> after List, we are saying this

list will hold integer objects. Similarly, when we use it after ArrayList,

it means the same thing. We’ll get into

more of what we can do with this sort of type specification later, but for now,

know that whatever type of data we are storing, we need to specify it in the

variable declaration using <>. For example, if we were storing Jeroo

objects we’d specify <Jeroo>, or <Pixel> if we were storing Pixel

objects.

You may also notice we used the word Integer instead of int. This has

to do with what are called “primitive types” versus objects. We’ll get more

into what the differences between these two things are later as well. For

now, just know that if you wanted to create an

ArrayList of doubles, you’d specify <Double>. For booleans,

you’d similarly use <Boolean>.

4.3.7.1.3. Adding Our Numbers¶

A List has a set of methods we can call. To add an item, we could use

the add() method.

List<Integer> list = new ArrayList<Integer>();

list.add(-2);

After this code runs, our list would look like this:

If we added another value…

list.add(8);

Our list would look like this:

4.3.7.1.4. Accessing List Items¶

Lets assume we’ve added all 15 numbers as seen in the diagram above to our list, but then wanted to access the second number.

To access the second item in our list, we would run code like this.

int x = list.get(1); // gets the second item in our list, which is 8

It is important to note that, even though this is the second item in our list, it is at index 1. This is because positions start at zero. The first item of a list will always be at index 0.

Indexing

For any List of length n, the first item will be at index 0, and

the last at index n - 1.

4.3.7.1.5. Changing Items¶

While we can use the get method to access any item in the list by

specifying its position, it only returns the value held in the list.

If we want to change the value stored at a given position, we cannot

use get(). For example, typing list.get(0) = 4; would not

successfully compile. It will not allow us to change the first item stored

in the list from -2 to 4. Instead, we need to use a different List method

to change an existing entry’s value.

list.set(1, 4);

When we call this set() method, we have to specify two things. First,

the location we want to change (its index or position). In our case, we are

trying to change the second item in our list, which is at index 1.

This first argument will always be a number.

We want to change the value of the second item in the list to 4, so that is

our second argument. If we’d had a list of Pixel objects and wanted to

use the set method, it may look like this:

Pixel p = new Pixel(1, 0);

list.set(1, p);

Keep in mind though that a list’s size is only as big as the number of items you have added to it. So the following code would break:

List<String> names = new ArrayList<String>();

names.add("Anna");

names.add("Joey");

names.add("Maria");

names.set(3, "Chris"); // error, since there is no index 3

The code above would compile, but would fail when you tried to run it. It

would produce an IndexOutOfBoundsException, which means that an illegal

index was provided (an index value that was negative, or went beyond the end

of the existing positions). Again, “Anna” is

stored at index 0, “Joey” at index 1, and “Maria” at index 2. This list

contains 3 items, but since it ends at index 2, the call to set() would

fail.

In short, if your code fails and you see an IndexOutOfBoundsException,

you’re trying to access a location in the list that does not exist.

4.3.8. Check Your Understanding: ArrayLists¶

4.3.9. Syntax Practice 8b: Lists¶

4.3.10. Nested For Loops¶

When iterating over Pixel objects in class thus far, we’ve done so like

this (assuming we had a Picture object named picture)

for (Pixel p: picture.getPixels())

{

// do some transformation

}

However, what if we wanted to change only every other Pixel? Or every

other row or column?

In these situations a counter controlled loop might be better.

Lets assume we know our picture is a rectangle of 100 pixels wide by 200 pixels

tall and we have a Picture variable called pic. We could write a

for loop like this.

int width = 100;

int height = 200;

for (int x = 0; x < width; x++)

{

Pixel p = pic.getPixel(x, 0);

p.setColor(Color.BLACK);

}

You’ll notice this code works through a series of Pixel objects, setting

their RGB value to black, or (0, 0, 0). However, this code will only work

through the top row of Pixel objects at y == 0. It

accesses the pixel at (0, 0), then (1, 0), all the way to (99, 0). However we

never use that height variable defined above and we never change the y

coordinate from 0. That’s perfectly ok if we only want to do one row. However,

if we want to do multiple rows, we need to do something more advanced. We

need a loop for the y coordinate as well.

int width = 100;

int height = 200;

for (int x = 0; x < width; x++)

{

for (int y = 0; y < height; y++)

{

Pixel p = pic.getPixel(x, y);

p.setColor(Color.black);

}

}

Much like conditionals, for loops can be nested.

In spirit (and in fact), we have combined two loops. One loop for x-coordinates repeats for each possible x value (each column of pixels in the image). The other loop for y-coordinates repeats for each possible y value (each row of pixels in the image).

Stepping through this code, when the exterior for loop starts,

x is initialized to 0 and we know 0 is less than 100 so we can start our

loop. Next, y is initialized to 0 which is less than 200, so our second

loop can start. With x at 0, the second for loop

increments y from 0 to 199. This means we’d access the pixel at (0, 0),

then (0, 1), all the way to (0, 199). Then the interior for loop would

terminate and the exterior for loop would

increment the value of x to 1. Then the whole process would repeat, this

time accessing the pixel at (1, 0), then (1, 1), all the way to (1, 199).

This process would keep going, repeating from the topmost y == 0 pixel for

a specific x, going vertically downward until reaching the bottommost y,

then advancing to the right in the x direction, until every pixel had been

processed.

This kind of structure is called a nested for loop. It is an extremely common pattern, particularly when using two variables to increment across a two-dimensional coordinate space, such as the two-dimensional grid of pixels in an image.